Commentary by Andy Brack | Take this column as a sign of things that are here.

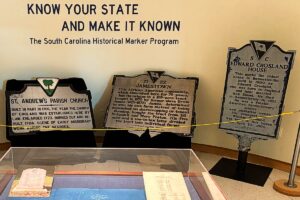

The S.C. Department of Archives and History on Dec. 5 unveiled a new exhibit in Columbia about those historical markers – signs – you see dotted across South Carolina’s landscape. The exhibit celebrates the state’s collection of 2,000 markers spread high and low – from Table Rock to the Temple of Sport in the Lowcountry.

The S.C. Department of Archives and History on Dec. 5 unveiled a new exhibit in Columbia about those historical markers – signs – you see dotted across South Carolina’s landscape. The exhibit celebrates the state’s collection of 2,000 markers spread high and low – from Table Rock to the Temple of Sport in the Lowcountry.

Eric Emerson, the agency’s director, said he’s constantly amazed at how much people enjoy the historic markers.

“In this age where everything is digital and apps and online and people want to access history digitally, that there is something tangible and out there in the public still generates interest among South Carolinians,” he said. “People love the program.”

Edwin Breeden, who coordinated the exhibit and helps to verify what’s on new markers, said the state’s marker program allows the department to partner with local groups to shine a spotlight on history and its relevance now.

“It makes people more aware of the ways that history is not just something that unfolds in other places,” he said. “It’s something that has real connections to places across the state.”

Back in 1936, the department, then called the S.C. State Historic Preservation Office, established the official state historical marker program. It’s one of the oldest programs of its type and, interestingly, isn’t filled with a bunch of hurdles. If a group wants a marker, it needs to do research, come up with wording, apply and be able to pay the $2,500 to $3,000 for the aluminum marker. But before the department gives its seal of approval, it verifies the information and ensures the proposal has local, state or national historic significance.

“We also usually do a lot of additional research,” Breeden said. “But it’s a fairly straightforward process.”

In an average year, the program approves 50 new markers. Here’s a look at some interesting ones:

First marker: Long Canes Massacre, Greenwood County. The program’s first marker actually commemorates a 1760 Cherokee attack on 23 settlers in McCormick County, but is physically located just over the county line.

First marker: Long Canes Massacre, Greenwood County. The program’s first marker actually commemorates a 1760 Cherokee attack on 23 settlers in McCormick County, but is physically located just over the county line.

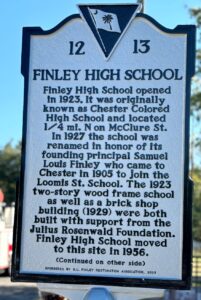

2,000th marker: Finley High School, Chester. The marker, unveiled in October, recognizes a 1950s-era equalization school erected during the state’s civil rights struggles. Alumni sponsored it. Gov. Henry McMaster, a big fan of the marker program, spoke at its dedication.

A favorite marker: Table Rock in Pickens County. “That was a really fascinating project to work on because it was for a natural feature,” Breeden said. “It was kind of challenging to tell the history that wasn’t just reciting geological facts.” It includes the social and cultural history of the mountain and how it became an icon for the state.

Reminder markers. Emerson said he is fascinated with markers in places that people wouldn’t know had history unless the markers were there. Examples are signs that denote Cherokee townships that have no trace today. Or a 2008 marker near Charleston International Airport that highlights the importance of a 1790s garden by French botanist Andre Michaux who imported plants that were tremendously important to American agriculture.

Odd marker: Mars Bluff atomic bomb accident, Florence County. In 1958, a U.S. Air Force jet with a nuclear payload accidentally dropped an unarmed bomb used for a nuclear payload. While the warhead was not installed, the bomb’s high explosives detonated on impact, leaving a huge crater and destroying a house. “It’s an unusual story that a lot of people aren’t aware of,” Breeden said. Emerson agreed.

Odd marker: Mars Bluff atomic bomb accident, Florence County. In 1958, a U.S. Air Force jet with a nuclear payload accidentally dropped an unarmed bomb used for a nuclear payload. While the warhead was not installed, the bomb’s high explosives detonated on impact, leaving a huge crater and destroying a house. “It’s an unusual story that a lot of people aren’t aware of,” Breeden said. Emerson agreed.

- To see the agency’s new free exhibit on markers, visit the department Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Location: 8301 Parklane Rd., Columbia, S.C. 29233. The exhibit is open through March.

Andy Brack is editor and publisher of Statehouse Report and the Charleston City Paper. Have a comment? Send to: feedback@charlestoncitypaper.com.