With warm weather and a booming economy attracting young families and aspiring college freshmen in record numbers, South Carolina might seem immune from the sweeping demographic and social challenges facing American higher education.

But even with those advantages, policymakers say the Palmetto State must start preparing now for a future with fewer college-aged kids, a graying workforce and increased skepticism about the value of pricey post-secondary degrees.

Leading the charge to bolster higher education to date has been S.C. Gov. Henry McMaster, who gently chided the state legislature over the summer for its refusal to fund a $3 million top-to-bottom review of S.C. higher education in the 2024-25 state budget.

“Despite the high demand for skills, training and knowledge, many colleges across the nation are seeing declining enrollments,” McMaster said in a July 3 letter to legislators. “I am hopeful you will reconsider next year. The time has come to evaluate whether the courses, degrees, and certificates that are offered at our public colleges and universities are meeting our state’s future workforce needs.”

To prepare, experts say S.C. must address a series of short-, medium- and long-term systemic challenges.

A looming ‘enrollment cliff’

More than 500 colleges and universities across the nation have closed or merged over the past 10 years as the total number of students fell by 10%, or 2 million students, The Wall Street Journal reported in August. And with the nation’s high school population set to begin a long period of decline in 2025 due to declining birth rates, even more could shutter in the decade ahead.

More than 500 colleges and universities across the nation have closed or merged over the past 10 years as the total number of students fell by 10%, or 2 million students, The Wall Street Journal reported in August. And with the nation’s high school population set to begin a long period of decline in 2025 due to declining birth rates, even more could shutter in the decade ahead.

The good news for prospective students is that falling enrollments are making it easier to get into competitive colleges, according to a recent evaluation by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI).

“While college enrollment surged during the 2010s, giving schools more leeway to reject applicants, the pendulum has now swung back,” AEI Fellow Preston Cooper noted last month. “Colleges are competing for a smaller pool of potential students, and as a result, those who do apply enjoy higher odds of admission.”

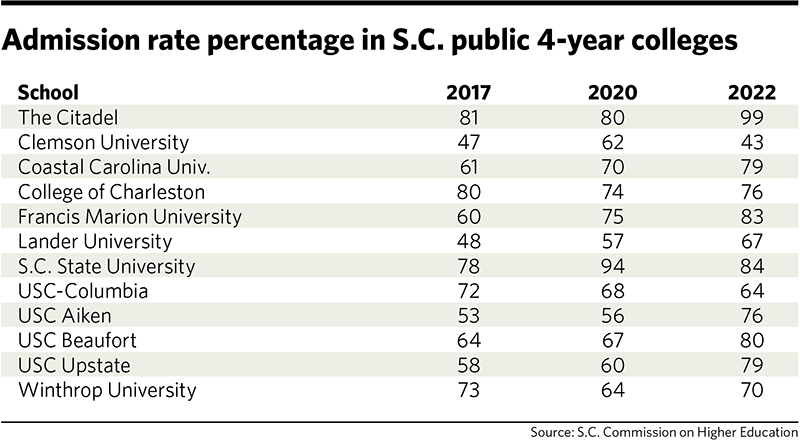

Despite rising application numbers and stable enrollments to date, South Carolina’s has seen the same trend, with overall acceptance rates rising from 55% to 65% at many state-supported colleges and universities since 2017, according to the S.C. Commission on Higher Education (CHE).

But as CHE President Jeff Perez observed in a Nov. 22 interview with the City Paper, that number is “highly variable” across the system, with schools like Clemson, the University of South Carolina in Columbia and the College of Charleston actually accepting a lower percentage of applicants over the same period of time.

Nevertheless, experts say South Carolina colleges are enjoying a temporary reprieve, not a permanent amnesty, from the larger American problem of declining birth rates and falling enrollments.

And the solutions, they argue, are clear: consolidation of existing state schools and a reduction in the number of programs offered – two of the policy prescriptions McMaster wants legislators to study.

Questions of governance

Some call South Carolina’s system of higher education governance decentralized. Others call it a collection of fiefdoms, with 33 largely autonomous public institutions competing for resources and making decisions that work for them but perhaps not for the larger system.

At a press conference earlier this year, McMaster seemed to go out of his way to raise this issue of governance, noting that South Carolina’s neighbor to the north manages its higher education system quite differently.

“States like North Carolina, for example, have a board that’s not like our Commission on Higher Education,” McMaster said. “It’s set up sort of the same, but they have the authority to change things.”

McMaster isn’t the first South Carolina governor to argue for more centralized authority over the system. In fact, former Gov. Mark Sanford called for an independent Board of Regents to oversee the state’s colleges and universities in the early 2000s, but the proposal died in the state legislature.

And while critics argue stronger central governance will be necessary to meet the coming demographic challenges, longtime Statehouse observers say the idea is likely to die again due to a mix of bureaucratic inertia and the influence of powerful university interests in the legislature.

Workforce development

Long a focus of South Carolina educational policy, workforce development took on an even larger future role with this year’s release of the Unified State Plan for Education and Workforce Development (USP). Developed in response to 2023’s Education and Workforce Development Act, the 44-page plan identifies more than 70 priority occupations that South Carolinians will need post-secondary degrees to fill in the years ahead.

“Knowledge is the fuel that powers South Carolina’s economic engine,” Perez said when the report was released. “Through the USP we will be part of this important undertaking to ensure South Carolina citizens can receive the post-secondary preparation that will equip them for success in whatever career they choose.”

McMaster, who typically frames educational issues in terms of jobs, lauded the report as an important first step.

“This plan will bridge the gaps between education, workforce, and economic development, preparing our citizens for the multitude of new jobs being created statewide,” McMaster said.

The question, according to experts, is whether the current system, given its long-term demographic and governance issues, can make even the best-designed plans work.

The state legislature is expected to again consider the governor’s request for a top-to-bottom review of higher education when it next takes up the state budget in March of 2025.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

I actually agree with McMaster. The legislature is very shortsighted and their constituents will suffer.