By Jack O’Toole, Capitol bureau | After a 13-year hiatus, the state of South Carolina is planning to resume executions this month amid an ongoing debate about the fairness, expense and effectiveness of capital punishment.

According to an Aug. 30 S.C. Supreme Court order, six death row inmates, four of whom are Black, have exhausted their appeals and can be executed by the state Department of Corrections (SCDC) at 35-day intervals. The men awaiting execution are:

- Freddie Owens, 46, convicted of murdering Greenville convenience store clerk Irene Graves in 1997. Owens later admitted to killing a Greenville County cellmate as he awaited sentencing for Graves’s murder. Owens’s execution is scheduled for Sep. 20.

- Richard Moore, 59, convicted of murdering Spartanburg convenience store clerk James Mahoney during a robbery in 1999.

- Marion Bowman, 44, convicted of murdering 21-year-old Kandee Louise Martin in Orangeburg in 2002.

- Brad Sigmon, 66, convicted of killing his girlfriend’s parents, Gladys and David Larke, in Greenville County in 2002.

- Mikal Mahdi, 41, convicted of murdering Orangeburg County Sheriff’s Office Captain James Myers in 2004.

- Steven Bixby, 57, convicted of murdering two law enforcement officers – Abbeville County Sheriff’s Office Deputy Danny Wilson and State Constable Donnie Outz – in 2007.

First possible execution since 2011

If Owens’s sentence is carried out as scheduled, he will be the 44th South Carolinian put to death since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, and the first since Jeffrey Motts, who was executed for the murder of his cellmate, Charles Martin, in 2011.

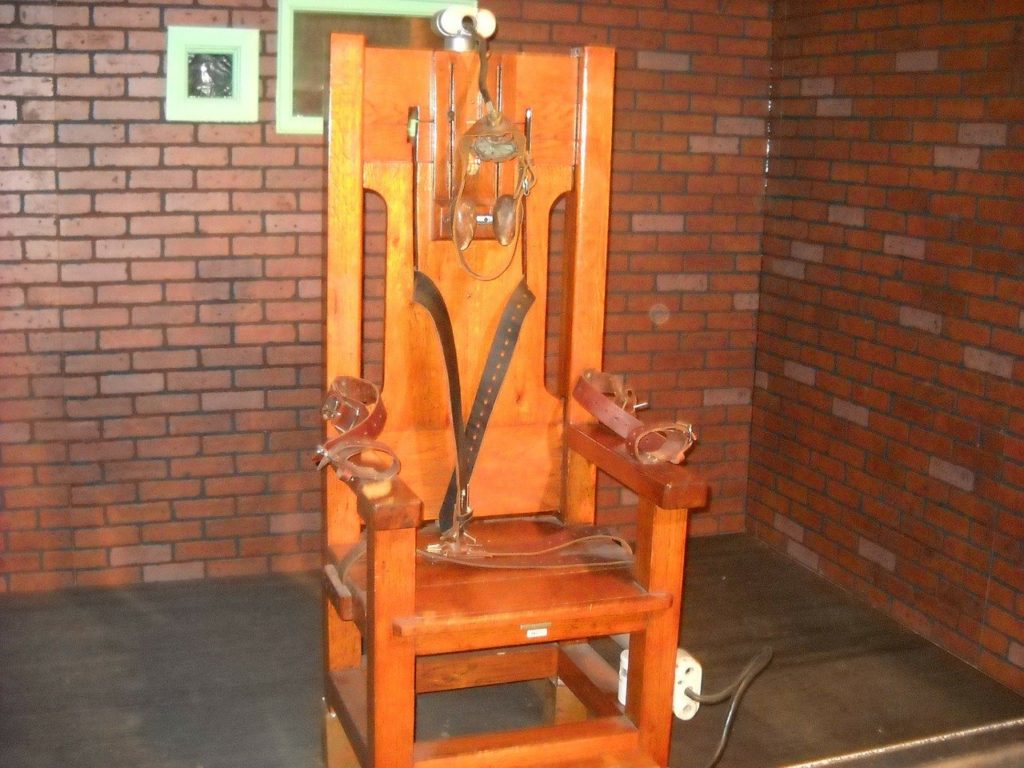

Since then, the state’s efforts to carry out death sentences have been stymied by pharmaceutical distributors’ hesitance to be seen providing drugs for states to use in lethal injections. To break the impasse, the S.C. General Assembly approved the legality of executions via the electric chair and then firing squads in 2021. Two years later, state lawmakers shielded drug providers from the risk of public exposure in 2023.

“Justice has been delayed for too long in South Carolina,” Gov. Henry McMaster said in a September 2023 statement after notifying the courts that the S.C. Department of Corrections had obtained the necessary drugs and was prepared to resume lethal injections as the primary method of execution. “This filing brings our state one step closer to being able to once again carry out the rule of law and bring grieving families and loved ones the closure they are rightfully owed.”

But with new questions about the death penalty currently swirling, and public support for the method at a 30-year low, according to a recent Gallup poll, opponents say it’s time to end the practice.

“Our state has real problems,” ACLU-SC spokesman Paul Bowers told the City Paper in a Sept. 3 interview, “and we’d all benefit if our politicians put as much energy into keeping people alive as they do into killing them.”

S.C.’s death penalty by the numbers…and one infamous case

South Carolina’s death penalty has long been plagued by questions of race, class, fairness, cost and more, as statistics maintained by the Death Penalty Information Center and South Carolinians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty demonstrate:

- Race: 74% of South Carolinians executed since 1900 have been Black, as are more than half of those currently awaiting execution.

- Procedure: Since the 1976 Supreme Court reinstatement, 60% of S.C. death sentences have been overturned due to court errors and prosecutorial misconduct.

- Innocence: Two death row inmates, Michael Linder and Warren Manning, have been exonerated and released since 1981. With 43 executions since 1976, that’s about 1 out of every 22 men executed.

- Geography: Four counties—Lexington, Greenville, Horry and Spartanburg—account for 51% of the prisoners on death row, with Lexington County responsible for almost 20%.

- Cost: Every inmate on death row costs South Carolina taxpayers more than $400,000 per year. Nationally, a death sentence has been found to cost between two and three times as much as a sentence of life without parole due to dramatically higher legal and incarceration expenses.

What critics say

Critics of capital punishment say the realities of those numbers were brought home in 2022 during South Carolina’s most infamous murder case, when S.C. Attorney General Alan Wilson announced that prosecutors would not seek the death penalty against longtime Hampton County attorney and powerbroker Alex Murdaugh.

Murdaugh, whose family essentially ran the county’s justice system for generations, was found guilty of murdering his wife and son and sentenced to life in prison in August 2023.

Wilson told The New York Times that the decision not to seek the death penalty was primarily driven by concerns about cost and the low likelihood that Murdaugh would ever be put to death.

“There are so many factors you have to consider,” Wilson said. “We felt like this case is complicated enough.”

At sentencing, S.C. Circuit Court Judge Clifton Newman, the Black man who presided over Murdaugh’s trial, noted the irony that Murdaugh and his family had sought the death penalty against more than 30 defendants during their time as county prosecutors.

“This case qualifies under our death penalty statute,” Newman said. “And as I sit here in this courtroom and look around at the many portraits of judges and other court officials, [I] reflect on the fact that over the past century, your family, including you, have been prosecuting people here in this courtroom, and many have received the death penalty, probably for lesser conduct,” Newman said.

South Carolina’s former U.S. Attorney, Bill Nettles of Columbia, said the Murdaugh case raises troubling questions about the state’s death penalty system.

“I don’t think there’s been nearly as fulsome a discussion as there should have been about why it is that people of color and less resources, having committed heinous but arguably not as heinous a crime as what Alex Murdaugh did, faced the death penalty and he didn’t,” Nettles told the BBC.

But does ‘state assisted homicide’ deter crime?

While death penalty advocates generally acknowledge there are problems with the system, they argue that some errors are inevitable in any human endeavor and that the deterrent effects of capital punishment are worth the price.

But research on the subject is mixed, with most recent studies finding that it has no measurable effect compared to a sentence of life in prison. In fact, in a 30-year head-to-head analysis, the murder rate was found to be significantly higher in death penalty states than in those without the death penalty.

In the end, though, critics of the death penalty like the ACLU-SC’s Bowers tend to set aside the numbers and speak of the human toll they say it takes on crime victims’ families, prisoners, executioners and members of the general public.

“We use sterile terms to talk about the death penalty, but it’s a brutal process that brutalizes everybody involved…including the people who work in execution chambers,” Bowers said. “The few [executioners] who’ve come forward have said it was a life-changing experience and not in a good way.”

One of those few was Craig Baxley, who told NPR in 2022 that he contemplated suicide after executing 10 men on South Carolina’s death row.

“Every single one of the death certificates says state-assisted homicide,” Baxley said. “And the state was me.”

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.