By Lily Levin | Lifelong Lowcountry resident Audrey Brown takes her 13-year-old son John regularly to Northbridge Park to fish. But when asked if she’d seen any advisories about eating fish caught there, she said she only read them “if [contamination] occurs and I come across it on my phone.”

Otherwise, Brown said she doesn’t seek pollution information, which she felt should be more accessible and convenient.

The S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC) recently conducted a study of water bodies across the state documenting high levels of harmful toxins called polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “forever chemicals” in local freshwater fish, crab and oyster tissue. But despite the data, the department has not issued any PFAS meal consumption advisories — a decision which leaves many who consume the Lowcountry’s fish unaware and unprotected.

DHEC has, however, released a general statement on forever chemicals in South Carolina fish, but it’s not specific to any dataset or location. The agency recommends that consumers “Eat only the filets of fish (discarding the organs).”

And it suggests anglers should “reduce the consumption of certain species including, but not limited to, largemouth bass, bluegill sunfish, red ear sunfish and black crappie” in all fishing areas throughout the state — a potentially confounding recommendation given that many of these species are found in otherwise unrestricted bodies of water.

High levels and mushy fish

Another Charleston fisherman named Mark, who preferred to be identified only by his first name, said although he’s at Northbridge to fish for sport, he knows people who might be affected by and are unaware of the scope of local PFAS contamination. Mark, too, didn’t know about DHEC fishing advisories or its fish tissue sampling for forever chemicals.

Charleston businesswoman Tia Clark, who owns Casual Crabbing, said she was informed about contamination only recently in an article, even though the issue directly affects her business — and her livelihood.

“Six years ago was the first time I ever caught and prepared my food,” she said. “I really, really need or have to have that be a part of my life. [It’s] non negotiable.”

Northbridge Park’s Ashley River waterfront is one area lacking restrictions, even though DHEC in October 2022 found an average of 2,900 parts per trillion (ppt) of PFAS in three crab tissue samples taken near the park.

That’s 725 times greater than the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) proposed drinking water maximum contaminant level (MCL). DHEC noted that “oysters and crabs appear to bioaccumulate less PFAS than fish because they eat much smaller organisms.” In other words, freshwater fish in that area — the same fish that some anglers are eating —might have even higher PFAS concentrations.

Brown explained her son once caught a bass from the Northbridge boat landing that entered rigor mortis immediately after being pulled out of the water. After she’d cooked the fish, its meat was mushy and barely palatable.

“That’s [PFAS is] probably why your bass was soft!” Brown exclaimed to her son.

What’s the source?

Downstream toward the peninsula and further away from DHEC advisory territory, crab tissue averaged 60,800 ppt PFOS, significantly higher than even the samples of freshwater fish.

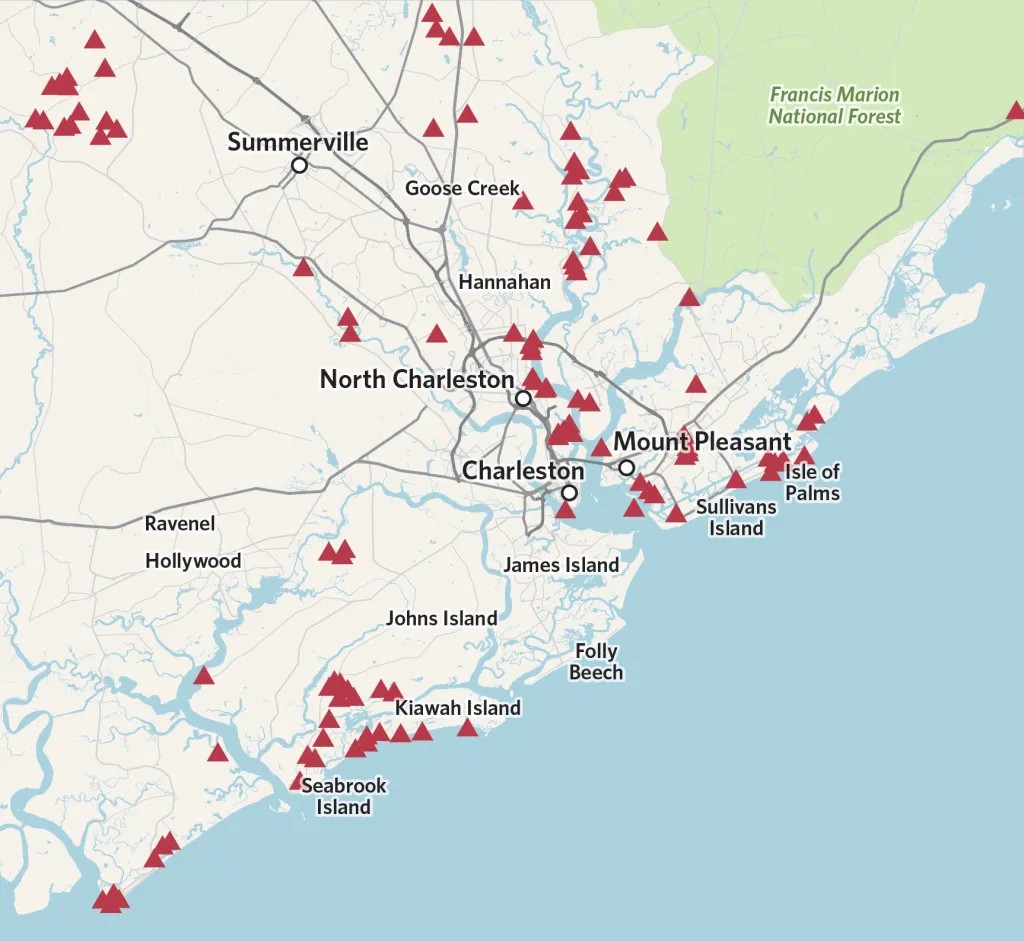

It’s hard to pinpoint where the contamination might be coming from because of lack of regulation, but a DHEC map of permitted sites for wastewater discharge and land application might offer a few ideas about potential polluters around the peninsula. The map, however, only accounts for currently permitted locations.

“The Ashley River was once lined with industrial factories, chemical plants, fertilizer production facilities and more, pumping hazardous chemicals and materials into the river, pluff mud and groundwater,” the City Paper reported last year.

Lifelong Charleston resident Lewis Harley said he has been fishing in area waters long enough to remember the nearby Albright & Wilson chemical plant explosion 32 years ago. That was before anyone was testing for PFAS contamination.

The explosion looked like a mushroom cloud and“it was right here on the harbor, further down the Ashley River,” he pointed.

Exposure risks

DHEC, in a statement, said the level of contaminants in South Carolina fish “don’t appear to be high enough to substantially affect most people’s overall” exposure to PFAS.

But regulatory standards in the neighboring state of North Carolina seem to suggest otherwise. According to N.C. guidelines, a blue crab with 2,900 PFOS ppt should only be eaten once per year — and a crab at 60,800 PFOS ppt should be avoided entirely.

What’s more, “The specific amounts of PFAS-contaminated fish that will impact a person’s health isn’t known at this time,” noted DHEC spokesperson Laura Renwick.

A 2022 study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, however, found if more places were actually testing patients regularly for PFAS concentration, only 2% of the U.S. population would have safe levels in their bloodstream. An estimated 89% would be at the orange level, necessitating increased screening for certain disorders and active PFAS reduction. The remaining 9% would be in the red level of highest risk: They’d need to reduce PFAS exposure and be assessed for “various signs and symptoms” of certain cancers, the paper said.

A 2019 study suggests the risk of hazardous exposure to PFAS may be particularly high for groups that know the land well and have witnessed various forms of industry-based contamination. This would include the Gullah/Geechee African American population, which is more reliant on subsistence fishing.

“Now we know, when we catch a bass, or a red, or whatever — throw it right back in,” Brown said.

- Lily Levin is a reporter for the Charleston City Paper, where this story first appeared. Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!