STATEHOUSE REPORT | ISSUE 22.29 | July 21, 2023

BIG STORY: S.C. again poised to be critical in presidential election

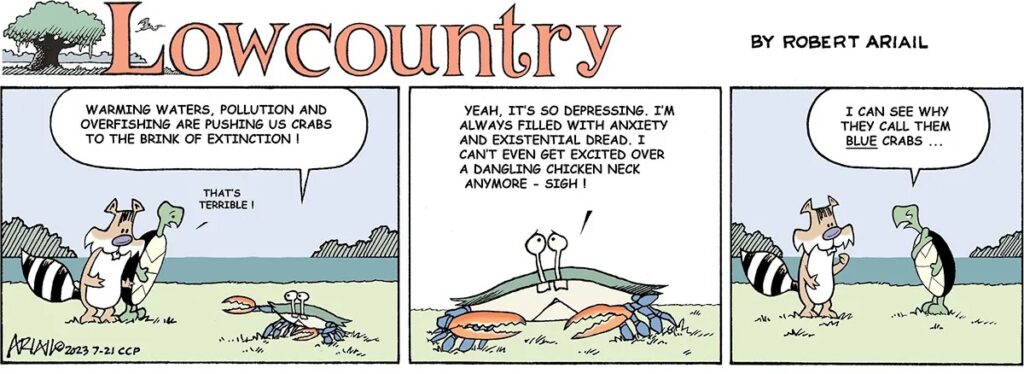

LOWCOUNTRY, Ariail: Crabby

COMMENTARY, Brack: The climate is changing and we need to act

SPOTLIGHT: AT&T

MYSTERY PHOTO: Towering presence

FEEDBACK: Send us your thoughts

S.C. again poised to be big in presidential election

Editor’s Note: Seasoned national political author Louis Jacobson offers a new look at how South Carolina has influenced and will influence national politics in this updated profile in the 2024 edition of the Almanac of American Politics. See the information at the bottom of the article to learn about a special limited offer to purchase this seminal work. Republished with permission.

By Louis Jacobson, Almanac of American Politics | In recent years, South Carolina has been vaulted into the headlines for tragic incidents and efforts at reconciliation. But in 2020, it helped elect a president, and in 2024, it is poised to vault to the head of the Democratic presidential nomination calendar.

Tragedy and coexistence have been dueling parts of South Carolina’s history from the beginning. The sugar-exporting island of Barbados, where the majority was enslaved, produced many of South Carolina’s original, non-indigenous settlers. Until 1855, South Carolina was the only colony or state with a Black majority. On the one hand, early Carolina plantation owners were tolerant of some groups, opening their colony to French Huguenots and Sephardic Jews. At the same time, they also owned giant plantations where slavery enabled the production of rice and indigo. South Carolinian Charles Pinckney led the effort to enshrine the principle of no religious tests for political office in the Constitution, yet he was also a slaveholder. Lowcountry planters maintained effective control of the legislature, and therefore the state’s two Senate seats and presidential electors, up through 1860. In that year and the next, South Carolina did more than any other state to precipitate the Civil War. In December, after the election of Abraham Lincoln, the South Carolina legislature voted to secede from the Union and was soon followed by other states. In April 1861, a cannon near Charleston fired on Union troops at Fort Sumter.

A post-war transformation

Defeat in the Civil War transformed South Carolina. Some 30 percent of military-age white males were killed, and one of the wealthiest states became one of the poorest. Reconstruction briefly gave Black Republicans political control, but the backlash was fierce once federal troops left; strict racial segregation and voting restrictions, including the poll tax, kept most South Carolinians disenfranchised for decades. As late as 1944, in a state of 2 million people, only 103,000 voted for president, with 88 percent of them voting Democratic. The Lowcountry languished in poverty, with malnutrition on coastal islands. A silver lining was architectural—the old mansions of Charleston were not replaced by commercial buildings, and instead were saved by the nation’s first local historic preservation movement (and rebuilt after Hurricane Hugo in 1989), cementing the city’s culture and civic pride. Mostly white Upstate South Carolina, with a growing textile industry, took the political lead, led by such politicians as Pitchfork Ben Tillman (governor 1890-94, senator 1895-1918) and a close friend’s son, Strom Thurmond (governor 1947-51, senator 1954-2003).

Defeat in the Civil War transformed South Carolina. Some 30 percent of military-age white males were killed, and one of the wealthiest states became one of the poorest. Reconstruction briefly gave Black Republicans political control, but the backlash was fierce once federal troops left; strict racial segregation and voting restrictions, including the poll tax, kept most South Carolinians disenfranchised for decades. As late as 1944, in a state of 2 million people, only 103,000 voted for president, with 88 percent of them voting Democratic. The Lowcountry languished in poverty, with malnutrition on coastal islands. A silver lining was architectural—the old mansions of Charleston were not replaced by commercial buildings, and instead were saved by the nation’s first local historic preservation movement (and rebuilt after Hurricane Hugo in 1989), cementing the city’s culture and civic pride. Mostly white Upstate South Carolina, with a growing textile industry, took the political lead, led by such politicians as Pitchfork Ben Tillman (governor 1890-94, senator 1895-1918) and a close friend’s son, Strom Thurmond (governor 1947-51, senator 1954-2003).

More recently, South Carolina has taken steps forward. During the civil rights era, most whites opposed integration, but unlike in Alabama and Mississippi, the effort was mostly not punctuated by violence. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ended legal segregation of public accommodations and workplaces and brought Blacks into the electorate. Democratic (and later Republican) Sen. Thurmond, who staged a record-setting filibuster of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, began appointing Black staffers and signed off on a Black federal judge. By the 21st century, the state elected Nikki Haley, a daughter of immigrants from India, and then Tim Scott, an African-American, to the House and later to the Senate, respectively; in this strongly conservative state, their ideology was what mattered.

Biggest changes in state have been economic

In many ways, the biggest change has been economic. Half a century ago, much of South Carolina’s economy depended on military bases and big textile mills in the I-85 corridor around Greenville and Spartanburg. Then, South Carolina became the most aggressive state in the South in seeking new industry. It advertised its business climate, with one of the nation’s lowest rates of unionization and taxation and a willingness to splurge on tax incentives; in 2021, only 1.7 percent of South Carolina workers were union members, the lowest in the nation.

Crucially, Democratic Gov. (later Sen.) Ernest Hollings spearheaded the creation of the state’s technical colleges, which today educate and train hundreds of thousands of residents a year. Michelin opened the first of several South Carolina plants in 1975, and the first BMW vehicles rolled off the Spartanburg assembly line in 1992. Volvo chose a South Carolina site 30 miles northwest of Charleston as the location of its first North American assembly plant, and Mercedes builds vans in North Charleston. Companies such as Bosch and Adidas have built factories throughout central and Upstate South Carolina.

In recent years, the state has led the nation in exports of tires and completed passenger vehicles. In 2022, BMW announced that it would invest more than $1 billion in its Spartanburg facilities to build electric vehicles and the batteries that power them. Smaller investments were announced by ZF Transmissions in Laurens County, south of Greenville-Spartanburg, and by Diversified Medical Healthcare and Trane Technologies Thermo King, both in Greenville. South Carolina has even secured a piece of the tech sector: Red Ventures, a $2 billion digital conglomerate that owns such brands as CNET, Lonely Planet, and Healthline, operates from a modern, 180-acre campus in Indian Land, south of Charlotte.

Navy bases were the mainstay of Charleston’s economy in the 1970s, but they were closed in the early 1990s and the area subsequently became a center of aircraft production. In 2009, Boeing chose North Charleston as the location of a plant where all of its 787 Dreamliners are assembled; it has experienced conflicts over unionization, quality issues, and the airline industry’s pandemic downturn, though business has ticked up recently.

Charleston is a major port, which is especially helpful for the state’s international exporters; in late 2022, the state completed a five-year, $500 million dredging project that enabled container ships to traverse the Charleston harbor regardless of tidal conditions. Charleston’s downtown has not only survived but thrived, thanks in large part to the creative energy of longtime Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr., who was first elected in 1975 and served for 40 years. With a keen aesthetic eye, he made the city’s historic center a magnet for tourists; statewide, tourism has grown consistently, passing the military’s statewide economic impact in 2016. In 2023, Charleston planned to open the International African American Museum at Gadsden’s Wharf, the entry point for an estimated 40 percent of enslaved Africans brought to the U.S.

Still, poverty and racial issues persist

Poverty persists in many areas of the state. South Carolina’s median income and its poverty rate both rank in the bottom 10 nationally. South Carolina ranks well below the median for the percentage of residents with a college degree.

Teacher pay has lagged; between 2020 and 2021, South Carolina was one of only two states that saw teacher salaries decline, along with Georgia and Idaho, though in 2022, lawmakers agreed to raise the minimum salary from $36,000 to $40,000.

South Carolina is also at risk from climate change; it has been hit regularly by hurricanes, most recently the tail end of Ian in 2022. One federal gauge near Myrtle Beach has shown sea levels rising 10 inches since the late 1950s, and at an accelerating rate.

Race has continued to be a defining issue for South Carolina. In 2015, Dylann Roof, a man with a history of white supremacist beliefs, entered a historic African-American church in Charleston, sat down for Bible study, then systematically gunned down nine Black worshippers—including the pastor, state Sen. Clementa Pinckney–as he squeezed the trigger more than 75 times. The attack took place in the successor to the very same church that was the epicenter of the 1822 slave rebellion led by Denmark Vesey, which ended with the execution of Vesey and numerous lieutenants, as well as the destruction of the church. (Before his death, Pastor Pinckney had been active in erecting a memorial to Vesey.)

Amid the mourning, a debate about old subjects—race and Confederate heritage—reemerged. Critics said the state should finally do what it had previously balked at: Remove the Confederate battle flag from the state capitol grounds in Columbia, where it had flown, in one way or another, since 1962. Haley, who prior to the killings had shown little interest in following her predecessors’ failed efforts to pull down the flag, offered her support for removal, and the tide turned. On July 10, 2015, the flag was permanently lowered from the statehouse grounds. Roof was sentenced to death in 2017, the nation’s first federal hate-crime defendant to face the death penalty; the Supreme Court denied an appeal in 2022.

But even today, South Carolina remains just one of two states, along with Wyoming, that has no hate crimes law. Black residents (along with environmentalists and others) continue to resist a $3 billion plan to widen an I-526 freeway interchange in a heavily Black neighborhood in North Charleston. And the successful 2023 murder prosecution of Alex Murdaugh, scion of a powerhouse legal family in Colleton County, shone a national spotlight on the historical power imbalances in this corner of the Old South.

People are moving to Palmetto State

Through the 1960s, few people except military personnel moved to South Carolina. That has changed in a big way. Since 2010, the population has grown by 14.2 percent, driven by migration from other states; South Carolina saw the 10th fastest population growth of any state in the 2020 Census. Growth has been hot on and near the coast—36 percent during the past decade in Horry County (Myrtle Beach), 33 percent in Berkeley County (northern suburbs of Charleston), 20 percent in Dorchester County (the northwestern suburbs of Charleston), and 18 percent in Beaufort County (Hilton Head) and Charleston County (Charleston).

Further inland, two suburbs of booming Charlotte North Carolina—York and Lancaster counties—have grown by 28 percent and 31 percent, respectively. Beyond these growth corridors, though, 24 largely rural counties saw population declines over the past decade.

Overall, the percentages of white residents (63 percent) and Black residents (27 percent) have remained stable, with relatively small populations of Hispanics (6.4 percent) and Asians (1.9 percent). The migrants include many affluent retirees who are eager to spend days with pleasant weather on the golf course, in a state with a modest cost of living; the share of senior citizens has increased from 12 percent in 2000 to 14 percent in 2010 to almost 19 percent today. By 2030, the state is expected to have more residents 65 and older than children in school.

Politics cleave along racial lines

The influx of white retirees has moved South Carolina politically toward Republicans. Politics cleave the electorate along racial lines, and the hard math of the population figures makes it difficult for Democrats to win statewide. South Carolina has voted Republican for president in every election but one since 1960—in 1976, when son of the South Jimmy Carter was running. But it’s South Carolina’s early primary that often plays a pivotal role, and few were more consequential than the Democrats’ in 2020. Coming off poor finishes in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada, Joe Biden bet everything on a win in South Carolina, and after U.S. Rep. James Clyburn, the state’s most influential Black Democrat, endorsed Biden three days before the primary, he ended up winning the state so convincingly that most of the remaining Democratic candidates fell in line.

Donald Trump—who had forged ties with such leading South Carolina Republicans as U.S. Sen. Lindsey Graham, Gov. Henry McMaster, Haley and future White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney—won the state easily in both 2016 and 2020, with his winning margin narrowing by only two points in 2020. Running alongside Trump, Graham managed to win reelection by double digits, despite a strong Democratic opponent in Jaime Harrison, a massive fundraising deficit, and lots of baggage accumulated during the Trump years.

The Democrats’ drought continued in 2022, when McMaster defeated a credible Democratic ticket by 17 points—double his margin four years earlier. No Democrat won more than 43 percent of the vote statewide, and setting aside Clyburn’s safe seat, no congressional Democratic candidate ran within 14 points.

After the 2022 election, Biden won approval by the Democratic National Committee to make South Carolina the Democrats’ first presidential primary beginning in 2024; beyond Biden’s personal loyalty, South Carolina satisfied the concerns of some Democrats that Iowa and New Hampshire lacked racial diversity. But some in the party worried about making such an uncompetitive state in the general election first in the nation.

LIMITED OFFER: For more than five decades, the Almanac of American Politics has set the standard for political reference books. Later this month, the Almanac will be publishing its 2024 edition, with some 2,200 pages offering fully updated chapters on all 435 House members and their districts, all 100 senators, all 50 states and governors, and much more.

Louis Jacobson, a senior author of the Almanac and a contributor to seven volumes, writes the 100 state and gubernatorial chapters. Here are the chapters he wrote for the Almanac about South Carolina and Gov. Henry McMaster.

Readers can receive a 15 percent discount if they purchase the 2024 edition through the Almanac’s website — https://www.thealmanacofamericanpolitics.com/ — and apply the code CCP15ALM at checkout. The offer is good through August.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@charlestoncitypaper.com

Crabby

Cartoonist Robert Ariail generally has a biting or funny comment about the great state of South Carolina in his weekly cartoon. Here’s what he’s thinking about climate change and existential dread. Love the cartoon? Hate it? What do you think: feedback@statehousereport.com.

Editor’s Note: Congrats to Ariail for winning first place in the Association of Alternative Newsmedia for best cartoon in its 2023 news contest.

The climate is changing and we need to act

Another Editor’s Note: Brack’s weekly column won first place as best political column in the 2023 news contest by the Association of Alternative Newsmedia.

By Andy Brack | As a south Georgia boy growing up in the 1960s, we’d occasionally see armadillos and brown thrashers, the state bird. Now that the climate is warming, the armadillos are marching north and are showing up in South Carolina yards. And who knows where the brown thrasher is – it’s no longer found in Georgia.

Climate change is everywhere. Ocean temperatures in Florida are being reported in the 90s, which seems unreal because air temperatures are cooler. The Florida Keys and Caribbean islands are having more coral bleaching from overheated waters. Blue land crabs, an invasive species in South Carolina, are coming out of burrow holes for higher land thanks to recent rains. And good gracious, the summers are hotter – just look at three weeks of 100+ degree days in Arizona – while the winters here generally have become milder.

Climate change is everywhere. Ocean temperatures in Florida are being reported in the 90s, which seems unreal because air temperatures are cooler. The Florida Keys and Caribbean islands are having more coral bleaching from overheated waters. Blue land crabs, an invasive species in South Carolina, are coming out of burrow holes for higher land thanks to recent rains. And good gracious, the summers are hotter – just look at three weeks of 100+ degree days in Arizona – while the winters here generally have become milder.

“Climate change is a real threat that the state and communities have to take action on – both reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and adapting and becoming more resilient to current and future challenges,” said John Tynan, executive director of Conservation Voters for South Carolina. “We’re already seeing more intense weather events that lead to more extreme flooding. But the impacts can be seen more subtly too – changing growing seasons, changing wildlife migrations, more sunny day flooding.”

Camden lawyer Tom Mullikin, who chaired Gov. Henry McMaster’s state Floodwater Commission, is also worried about what’s happening across South Carolina and the world. This month, he’s been hiking in the heat across the state with the SC7 expedition to raise awareness about what’s happening outside.

“I am concerned with the micro-manifestations of global climate change,” Mullikin said. “In South Carolina, those changes are mostly related to flooding, sea level rise, and associated coastal erosion and salt water intrusion. The macro atmospheric issue of climate change is one that is being addressed by South Carolinians through reduction of our anthropogenic [human] interference.”

The folks at the S.C. Coastal Conservation League say climate change has become the defining issue of our lives. So what can be done?

At the top of any list should be investing in the best-available science, said CCL spokesman Lily Abromeit.

“Our world is constantly changing, and we need the best and most up-to-date information to provide solutions for a dynamic environment,” she said. “From tidal gauges, groundwater monitoring and marsh migration mapping – we need to leverage science to inform how we adapt and respond to climate pressures, and put the funding mechanisms in place to achieve this goal.

Other important ideas for the state to move on:

Wetlands. Protect more isolated wetlands to serve as sponges for water and habitats, especially since federal courts stripped protections to favor developers, Abromiet said.

Cleaner energy. Replace coal power plants with clean energy generators, such as solar and stored sources from wind, Tynan said. Mullikin agreed, saying, “We need to invest in efforts to crack the code on advanced storage so that we can continue to move rapidly to sustainable energy.”

Boost efficiency. “South Carolina ratepayers have some of the highest energy bills in the nation — most of which is due to not using energy efficiently,” Tynan said.

Conserve land and plant more trees. “Each mature tree absorbs approximately 11,000 gallons of water annually,” Mullikin said. “These trees also sink 1 metric ton of carbon over the life of the tree.”

There’s a lot more that South Carolina leaders can do to keep its natural places special – and to show other areas of the world that it can be done. But first, everyone in the legislature needs to make climate and conservation a top priority – and then get to work. Let’s get to leading, legislature!

Award-winning columnist Andy Brack is editor and publisher of Statehouse Report and the Charleston City Paper. Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

AT&T

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. Today’s featured underwriter is AT&T Inc.

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. Today’s featured underwriter is AT&T Inc.

AT&T Inc. (NYSE:T) helps millions around the globe connect with leading entertainment, mobile, high speed Internet and voice services. We’re the world’s largest provider of pay TV. We have TV customers in the U.S. and 11 Latin American countries. We offer the best global coverage of any U.S. wireless provider*. And we help businesses worldwide serve their customers better with our mobility and highly secure cloud solutions.

- Additional information about AT&T products and services is available at http://about.att.com.

- Follow our news on Twitter at @ATT, on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/att and YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/att.

* Global coverage claim based on offering discounted voice and data roaming; LTE roaming; voice roaming; and world-capable smartphone and tablets in more countries than any other U.S. based carrier. International service required. Coverage not available in all areas. Coverage may vary per country and be limited/restricted in some countries.

Towering presence

Here’s a photo of a tower sent in by a reader, but where and what is it? Send us your guess of what this photo shows – as well as your name and hometown – to feedback@statehousereport.com.

Last week’s “Where is this wall?” got a bunch of responses from people who knew it was along King Street (near Calhoun St.) as part of Charleston native Shepard Fairey’s “Power and Glory” mural series from 2014. “Scattered across several walls, alleys and facades downtown, a powerful palette of red, black and gold dominates the series,” super sleuth George Graf of Palmyra, Va., shared. Others who correctly identified the mural were: David Lupo of Mount Pleasant; Frank Bouknight of Summerville; Elizabeth Jones and Jay Altman, both of Columbia; Pat Keadle of Wagener; Allan Peel of San Antonio, Texas; and Jacie Godfrey of Florence.

Last week’s “Where is this wall?” got a bunch of responses from people who knew it was along King Street (near Calhoun St.) as part of Charleston native Shepard Fairey’s “Power and Glory” mural series from 2014. “Scattered across several walls, alleys and facades downtown, a powerful palette of red, black and gold dominates the series,” super sleuth George Graf of Palmyra, Va., shared. Others who correctly identified the mural were: David Lupo of Mount Pleasant; Frank Bouknight of Summerville; Elizabeth Jones and Jay Altman, both of Columbia; Pat Keadle of Wagener; Allan Peel of San Antonio, Texas; and Jacie Godfrey of Florence.

>> Send us a mystery picture. If you have a photo that you believe will stump readers, send it along (but make sure to tell us what it is because it may stump us too!) Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com and mark it as a photo submission. Thanks.

Send us your thoughts

We encourage you to send in your thoughts about policy and politics impacting South Carolina. We’ve gotten some letters in the last few weeks – some positive, others nasty. We print non-defamatory comments, but unless you provide your contact information – name and hometown, plus a phone number used only by us for verification – we can’t publish your thoughts.

Have a comment? Send your letters or comments to: feedback@statehousereport.com. Make sure to provide your contact details (name, hometown and phone number for verification. Letters are limited to 150 words.

- ORDER NOW: Copies are in Lowcountry-area bookstores now, but if you can’t swing by, you can order a copy online today.

- Now available as an e-book!

ABOUT STATEHOUSE REPORT

Statehouse Report, founded in 2001 as a weekly legislative forecast that informs readers about what is going to happen in South Carolina politics and policy, is provided to you at no charge every Friday.

- Editor and publisher: Andy Brack, 843.670.3996

Donate today

We’re proud to offer Statehouse Report for free. For more than a dozen years, we’ve been the go-to place for insightful independent policy and political news and views in the Palmetto State. And we love it as much as you do.

But now, we can use your help. If you’ve been thinking of contributing to Statehouse Report over the years, now would be a great time to contribute as we deal with the crisis. In advance, thank you.

Buy the book

Now you can get a copy of editor and publisher Andy Brack’s We Can Do Better, South Carolina! ($14.99) as a paperback or as a Kindle book ($7.99). . The book of essays offers incisive commentaries by editor and publisher Andy Brack on the American South, the common good, vexing problems for the Palmetto State and interesting South Carolina leaders.

More

- Mailing address: Send inquiries by mail to: P.O. Box 21942, Charleston, SC 29413

- Subscriptions are free: Click to subscribe.

- We hope you’ll keep receiving the great news and information from Statehouse Report, but if you need to unsubscribe, go to the bottom of the weekly email issue and follow the instructions.

- Read our sister publication: Charleston City Paper (every Friday in print; Every day online)

- © 2023, Statehouse Report, a publication of City Paper Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.