By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | About 25 years ago, I ambled along the Yarra River in an urban park in Melbourne, Australia. It wasn’t a big deal until I realized I had absolutely no idea what was around me and what dangers lurked.

Instead of oaks and pines of the Southern coast, there were gray-green eucalyptus trees. I didn’t know much about Australia’s bugs or animals, although I knew it was a good idea to avoid any snakes. Birds sang, but I didn’t recognize their songs or what they were.

Instead of oaks and pines of the Southern coast, there were gray-green eucalyptus trees. I didn’t know much about Australia’s bugs or animals, although I knew it was a good idea to avoid any snakes. Birds sang, but I didn’t recognize their songs or what they were.

A two-hour walk from the suburbs to the city center along a river became an unexpected jaunt of looking over a shoulder here, speeding up there. It was a little creepy.

So imagine the harrowing experience of 12 million Africans uprooted from their homes and shackled by slavers into cramped, nasty boats for the two-month Transatlantic passage to the Americas. Almost 2 million died. Those who made it here to work on plantations to generate wealth for white settlers often lived in small shacks with no furniture to speak of and pallets or hammocks for beds.

And imagine the sounds they heard – shrieks of different birds, croaking of alligators, buzzing of mosquitoes and skittering of rodents. Ripped from their homeland into a life of slavery, their plight is almost unimaginable.

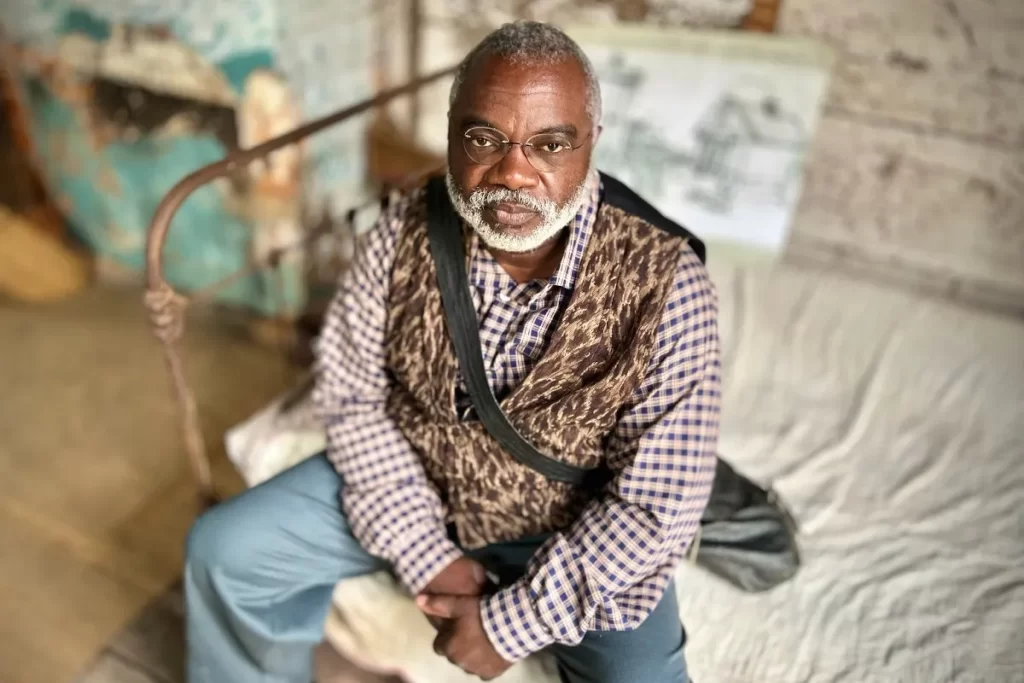

Except to Joe McGill, a Kingstree native and former park ranger who has spent the last few years sleeping in some of the remaining structures where enslaved Africans lived. Since he started the Slave Dwelling Project in 2010, he’s slept in more than 200 structures across 25 states.

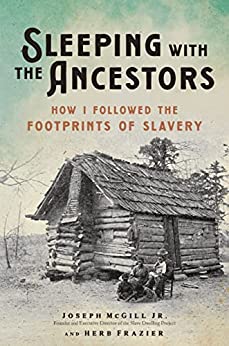

“Some had suggested that my experience would be like staying in a haunted house, but it wasn’t unpleasant at all,” he recalled in “Sleeping with the Ancestors,” a new book written by him and journalist Herb Frazier. “Hearing my own breath, I could imagine the men, women and children who had lived in the cabin [at Charleston’s Magnolia Plantation] during the decades of Jim Crow, when the opportunities of Reconstruction were pulled away from Black people. …

“Some had suggested that my experience would be like staying in a haunted house, but it wasn’t unpleasant at all,” he recalled in “Sleeping with the Ancestors,” a new book written by him and journalist Herb Frazier. “Hearing my own breath, I could imagine the men, women and children who had lived in the cabin [at Charleston’s Magnolia Plantation] during the decades of Jim Crow, when the opportunities of Reconstruction were pulled away from Black people. …

“I couldn’t sleep. Admittedly, it was a little spooky being alone in a former slave cabin and uncomfortable physically and psychologically. That night, I pondered what drove me to do such an odd thing. The ancestors!”

The point of sleeping in old cabins and dwellings where enslaved Africans once lived was to connect with the past in ways that haven’t made it into history books.

“My simple act of sleeping where enslaved people slept has broadened my awareness of their history, but it cannot replicate the pain and suffering they endured,” McGill wrote. “I hope that my travels have brought attention to the need for a deeper study and understanding of this history.”

For McGill, sleeping with the ancestors is no theoretical endeavor. It’s the opposite of the politically-charged, conservative talking points about so-called “critical race theory” that is upending our real history with vanilla-flavored versions of what happened.

McGill’s nightly encounters with hard floors, loud nature and dark skies seeped into his soul and informed him about how millions of people lived in the American South for more than three centuries.

He’s to be commended for broadening the way people think about history in the South, not branded as someone with a “woke agenda,” the popular current conservative term for people who want to avoid the reality of teaching a truthful, inclusive history to today’s children.

“I refuse to go back to that place where the youth of America are taught that enslavers were benevolent and enslaved people were happy,” he wrote in the book’s conclusion. “I’ve probably got more sleepovers behind me than I have ahead of me, but as long as I have a voice, I will continue to advocate for and love on the enslaved ancestors and tell their stories truthfully and respectfully.”

Good. “Sleeping with the Ancestors: How I followed the Footprints of Slavery” is available for $29.00 through Hachette Press.

Andy Brack is editor and publisher of Statehouse Report and the Charleston City Paper. Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!