By Herb Frazier | When I met Horace Mungin a decade ago on the beach at Sullivan’s Island, a kente cloth scarf draped his shoulders and a matching kufi cap adorned his head. I also wore our ancestors’ clothing, a waist-length garment made of coarse country cloth from Sierra Leone.

Horace was in the audience at Fort Moultrie Visitors’ Center during the annual Middle Passage Remembrance Program. I participated with a talk about my reporting trips to West African sites where our captured ancestors were held before they were shipped across the Atlantic.

Horace was in the audience at Fort Moultrie Visitors’ Center during the annual Middle Passage Remembrance Program. I participated with a talk about my reporting trips to West African sites where our captured ancestors were held before they were shipped across the Atlantic.

Horace liked my talk. When he greeted me on the beach, he said, “You the man!” I responded quickly, “No, brother. You the man!” My words could not be compared with the volumes of his edgy poems and essays on the Black experience in America.

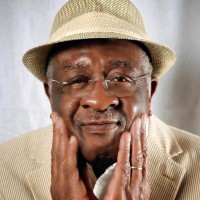

When Horace was about 5 years old his family left Hollywood, S.C., for New York City. While in the Bronx during the mid-1960s, he started writing poetry at the birth of the Black Arts Movement. In 2017, the National Museum for African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., included a video of Black Forum Magazine, which Horace founded in 1970. His magazine is a permanent part of the museum’s statement of the Black Arts Movement.

Mungin

Horace returned to the Charleston area in 1989 with his wife, Gussie, who’s also a South Carolinian. Horace continued to write. In 2020, Evening Post Books published his Notes from 169: A Poetic 400-year Reflection. In this collection of poems, Horace pushed against the injustices imposed by the conscious erasure of African American history.

Before Notes from 1619 was released, Horace emailed me and others in early November 2018 with an idea for a public event to address the harm done to people of African descent as a result of slavery’s legacy. He sought to pair his poems with essays written by others then hold conversations on topics that are uncomfortable for some.

He asked McLeod Plantation if it would stage the event. He called the presentation: “Black History for White People Only.”

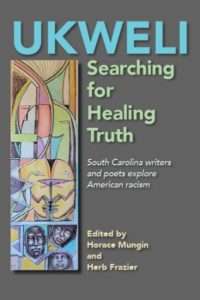

McLeod agreed to the five-part lecture-poetry series, but his title was too jarring. Horace settled on: “Ukweli: Searching for Healing Truth.” ”Ukweli” is the Swahili word for truth. The event began in early 2020. The pandemic interrupted it, but it resumed later that year.

Then Middleton Place invited Horace to bring a Ukweli topic on Black women to its site. When he told me this, I was surprised and inspired. I told him this lightning must be captured in a bottle. Let’s do a book of poetry and essays!

Then Middleton Place invited Horace to bring a Ukweli topic on Black women to its site. When he told me this, I was surprised and inspired. I told him this lightning must be captured in a bottle. Let’s do a book of poetry and essays!

“Yeah, an anthology of poems and essays aimed at awakening the ignorant and the misinformed about the truth (Ukweli) of the racial divide in America,” he wrote in an email. “You should plan on being the editor to solicit, select, and format the anthology.” I was immediately enthralled, but I insisted he must co-edit it with me. After all, Ukweli was his vision, not mine.

Now, Ukweli: Searching for Healing Truth, South Carolina Writers and Poets Examine American Racism will be released at 11 a.m. Saturday at McLeod Plantation Historic Site on James Island. Hurrah!

Ukweli is a collaboration with 47 of the best essayists, poets and thinkers in South Carolina and those who know its history. Horace and I were awed by how quickly this racially diverse team embraced Ukweli. They explore the Black experience in America from different perspectives, examining sensitive social topics through objective analysis and personal stories.

We also were grateful to Evening Post Books for moving Ukweli from an idea to a book.

When Ukweli is unveiled, Horace won’t be with us. He passed away Sept. 25, 2021. Gussie will stand with us as we remember Horace and celebrate Ukweli. It’s his vision. He’s the man!

Herb Frazier, a former reporter at The Post and Courier and noted local author, is special projects editor at the Charleston City Paper, where this commentary first was published. You can purchase the book for $29.95 online at: EvePostBooks.com. Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.