By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | There’s a big difference between knowing something, understanding it and doing something about it.

The coronavirus pandemic illustrates this trichotomy perfectly. For example, we know it’s smart to wear masks to reduce transmission of the virus. But if you walk around any bar, restaurant or grocery store in South Carolina today, it’s clear we don’t understand the reality. Rather than doing what we know is right (to keep wearing masks), we ignore what we know and act as if everything is hunky-dory.

The coronavirus pandemic illustrates this trichotomy perfectly. For example, we know it’s smart to wear masks to reduce transmission of the virus. But if you walk around any bar, restaurant or grocery store in South Carolina today, it’s clear we don’t understand the reality. Rather than doing what we know is right (to keep wearing masks), we ignore what we know and act as if everything is hunky-dory.

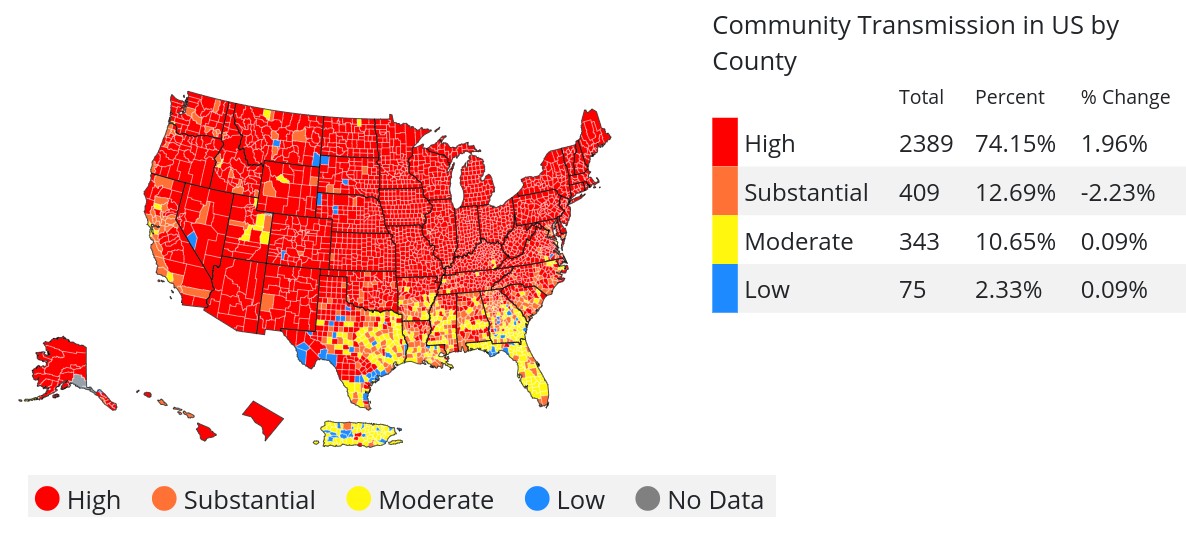

It’s not. If you routinely watch a map of virus hot spots, it’s crystal clear the virus is about to make another surge in South Carolina. A map of the United States, for example, shows a slow approach of the virus toward us from states with high levels of COVID-19. Right now, for example, South Carolina has a comparatively low rate of positive coronavirus tests — in the 5 percent range over the last couple of weeks.

But look at where it’s already gotten cold — places like the Dakotas and Minnesota. Because winter weather has returned, people are inside more and living in closer proximity, causing infection rates to surge so much that some mask mandates are back.

It’s fairly obvious that the fourth surge is headed our way, probably just in time for Christmas. But people in South Carolina, where leaders never have taken public health warnings too seriously, will do what they’ve done in the past — ignore simple behavioral changes that can save lives. More people, particularly those who refuse to get a vaccination, will die. It’s as clear as the nose on your face.

The odd thing about ignoring the reality of this disease is people have known for years how to protect themselves. A century ago during the great flu pandemic, masks were a part of American culture. The difference between now and then is that people had a sense of common good, as compared to today when the notion of individual freedom at all costs trumps any general good to society.

Ever heard of the English village of Eyam in Derbyshire? Its citizenry figured out 350 years ago how to protect other villages from spreading bubonic plague. To this day, it’s considered a case study in how to prevent disease.

In Eyam, the plague arrived in August 1665 when a bundle of flea-infested cloth arrived for a tailor. Plague-infested fleas started biting people and they died. Over the next 14 months, some 260 people out of 800 in the village — almost one in three — died horrible deaths. But two priests developed a plan to try to stop the spread of the disease. Villagers agreed to quarantine, allowing no one in or out until the disease had run its course. Next they closed the church and held outdoor services. They stopped burying dead in the graveyard and buried them quickly after they died on land near where they died. Finally, supplies from merchants and other villages were left outside the quarantine zone and paid for with money that had been soaked in vinegar. By November 1666, there was no plague in the village and it had not spread to neighboring populations.

The example from Eyam shows how uneducated people were able to beat the disease by following protocols that were new to them, but known far and wide today: quarantining, not getting too close to others, having air flow in interactions and disinfecting things.

If they can do it, we can too by using the guidelines of modern science more effectively: wear a mask in public places; wash your hands frequently; maintain social distancing; and don’t gather in large groups. And for goodness sake, get vaccinated — something people in Eyam didn’t have.

Another surge is on the way. Let’s beat it by acting on what we know, instead of ignoring it.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.