An old electric chair in Texas. Photo via Wikipedia.

By Sam Spence, special to Statehouse Report | More than a century after South Carolina turned to a relatively new technology to execute people by electrocution, state officials are still trying to figure out the best way to end the lives of citizens sentenced to die at the hands of the government.

A new option for which there are no rules yet: a firing squad.

“We’re looking at best practices and what’s been done in other places to create our policies and procedures,” department spokesperson Chrysti Shain told the Charleston City Paper.

South Carolina law gives condemned criminals the ability to choose the method by which they will die. Until this year, the default was lethal injection. Death by the electric chair was the second option. But as public support for capital punishment waned, pharmaceutical companies became unwilling to ship the deadly cocktail of drugs to states needed to end a life.

After a decade of clamoring to figure out how to restart executions, South Carolina legislators finally passed a bill this year that reconfigured the state’s death penalty rules. Electrocution is now the state-endorsed execution method if lethal injection isn’t available. The new law introduced the third option, death by firing squad.

With an amended statute nominally in place, state-retained lawyers notified the S.C. Supreme Court on May 19 that the state Department of Corrections “is now able to carry out executions by electrocution.”

Brad Sigmon, convicted of a 2002 double murder in Greenville County, was the first scheduled. But with lethal injection unavailable and the state’s new firing squad not yet assembled, the high court vacated Sigmon’s execution order.

Executions seem unlikely until the firing squad policy is in place. It is, however, on the way.

A look back more than a century

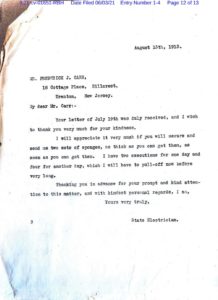

Letters filed in federal court by Sigmon’s attorneys show South Carolina’s state electrician seeking basic guidance soon after the state adopted execution by electrocution from his counterpart in Massachusetts.

“I will appreciate any literature or drawings of your chair and electric apparatus, also of the death chamber,” Tench Boozer wrote in March 1912 to the Massachusetts state electrician.

“I will appreciate any literature or drawings of your chair and electric apparatus, also of the death chamber,” Tench Boozer wrote in March 1912 to the Massachusetts state electrician.

S.C. purchased its new electric chair in May 1912 from New Jersey-based Adams Electric Company at a cost of $2,800, according to The (Charleston) News and Courier. The apparatus required additional electricity at the penitentiary when power itself was still relatively scarce — some rural areas of South Carolina would not be electrified for 20 more years.

By all accounts, the chair purchased in 1912 is the same one used today, though some electrical components have been updated.

Boozer was appointed to his post in 1911 by Gov. Coleman Blease, notorious in his own time as an amoral demagogue. Blease’s naked populist appeals to middle-class white mill workers and urban anti-prohibitionists alike turned off even Ben Tillman, the violent, virulent former governor and U.S. senator.

And while lynching and state factories devoid of health and safety laws were OK in Blease’s book, death by hanging at the hands of the state was just too much.

“It seems to me that this is a much more humane manner of execution than the barbaric form of hanging,” Blease wrote to lawmakers Jan. 9, 1912, according to The News and Courier.

The law swapping the electric chair for the gallows was later hailed in the paper as “one of the most important measures passed by the General Assembly in many years.”

The day South Carolina’s new execution law was passed, two men were sentenced to death by electrocution. By June, there would be at least four others, according to news reports. Five were Black, one white.

Many of those disparities are still with us today. More than half of South Carolina’s 37 death row inmates are Black, according to the Department of Corrections, while Black South Carolinians make up just 27 percent of the population.

Execution protocols

Access to current state execution protocols is “restricted,” Shain told the City Paper. But 2002 procedures also marked “Restricted” — obtained as part of a Freedom of Information Act request and filed in federal court by Sigmon’s attorneys — mapped out, down to the minute, how executions were carried out in the Palmetto State at that time.

On the day of their execution, inmates set to die by electrocution had their head and lower-right leg shaved, took a shower and wore pants cut off at the knee (to ensure contact with conducting strips on the chair). Once inside the execution chamber, the inmate was strapped in and outfitted with a leather cap studded with a brass electrode and lined with copper mesh and a sponge soaked in ammonia chloride.

At the appointed time, three executioners chosen from SCDC employee volunteers stand behind a one-way mirror facing the condemned inmate. Each pushes a red button at the far end of the room. All three buttons are capable of starting the deadly 2,000-volt cycle, according to another SCDC document, “but only one is active during an execution” — a psychological sleight of hand.

Rules for South Carolina’s new alternative, the firing squad, are being modeled after three states that still use firing squads, including Utah. There, five firing squad officers stand 25 feet from an offender. Each gets a loaded rifle. One is blank, so no one knows who will fire the fatal bullet.

“A punitive culture”

From her time as a criminal defense attorney, Cameron Blazer of Mount Pleasant describes a “deeply punitive” justice system that prioritizes retribution over prevention.

“I, every day, am up against that punitive culture in our criminal justice laws and in the environment of criminal justice. And it extends far beyond the most serious part of criminal punishment,” Blazer told the City Paper.

Gov. Henry McMaster noted the adjusted state law could be some consolation to victims’ families and loved ones.

“This weekend, I signed legislation into law that will allow the state to carry out a death sentence. The families and loved ones of victims are owed closure and justice by law. Now, we can provide it,” he tweeted recently

But that closure may still be elusive, Blazer said, with each death penalty case drawing close scrutiny and challenges.

“The finality that people desperately seek, when they have been through an awful tragedy, is not going to come to them in any speedy fashion through the death penalty, nor can it or should it, given how bad we are at imposing it.”

An earlier and longer version of this story first appeared in the Charleston City Paper, where Spence serves as editor. Have a comment? Send to feedback@statehousereport.com

BIG STORY: State scrambles again to develop new execution method

Statehouse Report· 07/16/2021 11:02 was quite informative. Thanks.