INSIDE ISSUE 19.25 | June 19, 2020

BIG STORY: Four-fifths of current lawmakers haven’t voted on Heritage Act

BIG STORY: Four-fifths of current lawmakers haven’t voted on Heritage Act

NEWS BRIEFS: Lucas announces justice, law enforcement committee

COMMENTARY, Brack: Repeal the Heritage Act next week

SPOTLIGHT: Riley Institute at Furman University

MY TURN, Leventis: Strong federal oversight is key to solving discriminatory policing

FEEDBACK: Hooray for one column; Too far on other

MYSTERY PHOTO: Imposing statue

S.C. ENCYCLOPEDIA: Voting Rights Act

Four-fifths of 2020 lawmakers haven’t voted on Heritage Act

By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | Only 30 of the state’s current 170 legislators cast votes 20 years ago on whether the state should protect monuments from removal. That means more than two-thirds of the members of the General Assembly have yet to weigh in on the controversial Heritage Act that effectively prevents any changes to public memorials.

The Heritage Act, put into law in 2000 as part of a compromise to move the Confederate flag off the Statehouse dome, has made recent headlines as protests around the nation seek to address systemic racism and police brutality. For protesters, monuments of Civil War soldiers, slavery proponents and others that fill courthouse squares and parks are visible reminders of the so-called “lost cause” of the Confederacy.

“Let’s take that statue down,” Charleston Democratic Rep. Wendell Gilliard said of Charleston’s John C. Calhoun statue earlier this month in response to national protests.

On Wednesday, the fifth anniversary of the slaying of nine worshippers at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston by a white nationalist, the city’s mayor, John Tecklenberg, and officials said Wednesday vowed to remove Calhoun’s statue from land owned by a militia organization with state appointees.

Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin announced last week that the city’s statue of Columbus was put in storage indefinitely, saying it would prevent the statue from being dismantled by protesters. In Virginia, protesters have toppled statues of Christopher Columbus and Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, and a monument to a Confederate artillery unit.

The Heritage Act passed 37-6 in the Senate April 12, 2000, with two members not present in the Senate and one member not voting. Eleven senators who served in the chamber in 2000 are there today.

The following month, House members voted 63-56 to pass the act on May 10, 2000. Two members were absent in the House and three members did not vote. Sixteen House members who voted on the bill in 2000 serve in the legislature today, three others now serve in the Senate. Click here to see how members voted in 2000.

The law passed as a compromise to deal with the Confederate flag after years of tension over its continuing presence at the Statehouse. Some analysts point to Republican Gov. David Beasley’s 1998 re-election loss to Democratic gubernatorial nominee Jim Hodges was due to Beasley’s call to take down the flag.

The Heritage Act did the following:

- Moved the Confederate battle flag from atop the Statehouse dome to a Confederate memorial on the Statehouse grounds;

- Removed three battle flags from the inside of the Statehouse;

- Created an African American monument at the Statehouse; and,

- Mandated that any future decisions regarding memorials on public property must be decided by a two-thirds vote by the House and Senate. Those memorials include African American and Native American, and those commemorating wars, including the Civil War. Read section 10-1-165 here.

The two-thirds vote mandate has been used only once in 20 years. Five years ago, after a white supremacist gunned down nine black people in a Charleston church, the legislature gave into a groundswell seeking to remove the the remaining Confederate flag on the Statehouse grounds.

House Speaker Jay Lucas, R-Hartsville, said in 2015 he would not make any further considerations under the act during his tenure. Lucas also voted to approve the original Heritage Act.

Of the 30 who cast votes in 2000 and remain in the legislature, 17 voted for it and 13 voted against it. Twelve of those dissenting votes come from current House members.

‘Start of a process’

Democrats in the Senate today say that in 2000, they saw the Heritage Act as their one chance to remove four Confederate battle flags from the Statehouse and they took it — knowing that it would be the start of a long process.

The original bill was sponsored by Charleston Democratic Sen. Robert Ford, a longtime civil rights activist. The flag went up on the Statehouse dome in 1962, as a commemoration of the Civil War’s centennial. It would remain there for 38 years before Ford’s legislation ultimately brought it to the Statehouse lawn.

Hopkins Democratic Sen. Darrell Jackson said it “pained” him to go to the Statehouse and recite the Pledge of Allegiance with the Confederate flag in the Senate chamber.

For years, Democrats had tried and failed to gain Republican support to have the flags removed. After a NAACP boycott of the state, Charleston Republican Sen. Glenn McConnell, who later became lieutenant governor and president of the College of Charleston, worked with Ford on a compromise bill that would lower the flag, remove the other flags and protect other memorials. Both men no longer serve in the General Assembly. Ford resigned his seat in 2013 and later pleaded guilty to misusing campaign donations.

“You’re protecting the Confederate monuments but also African American monuments,” Ford told Statehouse Report. “That’s the way the legislative process works, but 25, 30 years later you can’t act like you’re mad.”

Jackson said the deal was the “start of a process.”

“Isn’t that what compromise is about? That no side is a clear winner,” he said. “I knew eventually one day that flag would be removed from the dome, and removed from the yard one day also. I am even more fortunate to have been in the General Assembly to have witnessed that. It thrills me to see the debates as it related to abolishing the Heritage Act.”

Democrats in the House, who battled the bill on the Statehouse floor, still believe it is a problematic law.

“It was clearly problematic at the time, and we know you cannot bind future assemblies and that’s exactly what the Heritage Act sought to do,” House Minority Leader Todd Rutherford, D-Columbia, said. “I thought it ignored history and what we know about South Carolina’s history.”

Rutherford urged Charleston officials to move forward not to wait for the General Assembly to act.

‘The rebels will yell’

Many of the Republicans who voted on the bill — for and against — did not return calls seeking comment this week. But a few had their speeches on the floor in 2000 inserted into the official legislative record in the House and Senate journals. Here is how they explained their votes:

- Gaffney Republican Sen. Harvey Peeler voted against the bill, saying he loved the flag for his heritage. “You have the hate group and the heritage group. The heritage group, of which I am a member, the Sons of Confederate Veterans, see the flag as I see the flag with honor and respect.” He closed his speech with: “If you take that flag down tonight, in the morning, the rebels will yell. Race relations will not be the same in this state in my lifetime if you take that flag down.”

- U.S. Congressman Joe Wilson, R-District 2, served in the Senate at the time and voted against the Heritage Act. “I disagree with the compromise,” he said. “I feel very strongly about the wonderful and positive heritage of the people of South Carolina. Another concern that I’ve had is the divisions between the races in South Carolina.”

- Walhalla Republican Sen. Thomas Alexander voted for the bill. He commended his colleagues for discussion on the issue that has been “very heavy upon our hearts.”

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

Lucas announces justice, law enforcement committee

By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | The House has a new special committee to address law enforcement training and accountability, police seizures, criminal process and sentencing. House Speaker Jay Lucas, R-Hartsville, announced the committee Thursday, saying it will “address the urgent issues” raised in recent weeks, apparently alluding to nationwide protests.

“The S.C. House of Representatives has always been the people’s house,” Lucas said in a statement. “It will remain so by being the place where all viewpoints are expressed, heard and considered and where meaningful, open debate occurs. These challenging times are no exception.”

For weeks, people around the state and nation have been protesting systemic racism and police brutality. The protests were sparked by back-to-back incidents of unarmed black people being killed by police or while in police custody.

Lucas’ announcement comes two weeks after North Charleston Democratic Rep. Marvin Pendarvis invited protesters to the Statehouse, including the coming June 24 and 25 session, to push for legislative change. Read the story here. Members of the S.C. Legislative Black Caucus have also announced they want better state funding of body cameras and passage of a hate crimes bill.

A new Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) poll released this week found 71 percent of black Americans say they’ve experienced some form of racial discrimination or mistreatment during their lifetimes – including nearly half (48 percent) who say at one point that they felt their life was in danger because of their race. Two in five black Americans said they have been stopped or detained by police because of their race, and one in five black persons said they have been a victim of police violence.

The protests have proved popular, according to the KFF poll. Nearly two-thirds of respondents said they support the recent protests against police violence. Respondents also overwhelmingly supported law enforcement changes:

- 95 percent supported requiring police to intervene and stop excessive force being used by other officers and to report those instances;

- 89 percent supported requiring police to give a verbal warning, when possible, before shooting at a civilian;

- 76 percent supported requiring states to release disciplinary records publicly for law enforcement officers; and,

- 73 percent supported allowing people to sue police officers if they feel they were subjected to excessive force.

Earlier this week, U.S. Sen. Tim Scott, R-South Carolina, and Republican senators proposed policing changes with the Just and Unifying Solutions To Invigorate Communities Everywhere Act of 2020, or JUSTICE Act. The federal bill is a direct response to the massive public protests over the death of George Floyd and other black Americans, and it includes enhanced use-of-force databases, restrictions on chokeholds and new commissions to study law enforcement and race. Read the bill here. Last week, Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives released a much tougher proposal. Read more here.

The S.C. House Equitable Justice System and Law Enforcement Reform Committee is co-chaired by House Majority Leader Gary Simrill of Rock Hill and House Minority Leader Todd Rutherford of Columbia. The members will examine: Law enforcement officer training, tactics, standards and accountability; civil asset forfeiture, criminal process and procedure; and sentencing. Members include: Reps. Beth Bernstein, D-Columbia; Chandra Dillard, D-Greenville; Shannon Erickson, R-Beaufort; Wendell Gilliard, D-Charleston; Chris Hart, D-Columbia; Max Hyde, R-Spartanburg; Mandy Kimmons, D-Ridgeville; Cezar McKnight, D-Lake City; Chris Murphy, R-Summerville; Weston Newton, R-Bluffton; Tommy Pope, R-York; Garry Smith, R-Simpsonville; Leon Stavrinakis, D-Charleston; Ivory Thigpen, D-Columbia; Will Wheeler, D-Bishopville; and Chris Wooten, R-Lexington.

In other news:

![]() S.C. spiking with COVID-19 cases. South Carolina is in its second week of nearly daily records of confirmed coronavirus cases as testing has expanded but also the state has continued with its reopening plan. S.C. health officials announced 987 new cases and four deaths on Thursday, bringing the total to 21,533 confirmed cases and 621 deaths. “It is essential that each of us, every day, wear a mask in public and stay physically distanced from others,” State Epidemiologist Linda Bell said Thursday.

S.C. spiking with COVID-19 cases. South Carolina is in its second week of nearly daily records of confirmed coronavirus cases as testing has expanded but also the state has continued with its reopening plan. S.C. health officials announced 987 new cases and four deaths on Thursday, bringing the total to 21,533 confirmed cases and 621 deaths. “It is essential that each of us, every day, wear a mask in public and stay physically distanced from others,” State Epidemiologist Linda Bell said Thursday.

- Gov. Henry McMaster is unlikely to mandate mask wearing, but health experts say it could help slow the spread without exacting huge economic tolls. Read more from our coverage last week.

House, Senate scheduled to meet. The official chamber calendars show the Senate will meet noon June 23, and the House will meet 1 p.m. June 24. Tuesday’s Senate meeting will address its Finance Committee recommendation for CARES to send over to the House before it convenes. June 25 will be a back-up day for the House if business is not completed on June 24, according to the House Clerk’s office. The Senate will schedule its meetings day-by-day depending on the House’s meetings, according to the Senate Clerk’s office. Calendar for the Senate here. Calendar for the House here.

Ways and Means to look at CARES spending June 22. The House Ways and Means Committee convenes virtually 2 p.m. Monday via Teams, a virtual meeting service. The meeting is information-only regarding the Executive Budget Office’s recommendation for federal coronavirus aid. The public will be able to stream the meeting but no comments will be taken. Agenda here.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

BRACK: Repeal the Heritage Act next week

By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | The curious thing about laws is they can be repealed.

When South Carolina legislators meet two days next week to talk about money, they need to add repealing the Heritage Act to the agenda. Twenty years ago, the act passed as the fulcrum of a compromise to remove the Confederate battle flag from the Statehouse dome. Now, its time has come. It needs to be shelved itself, gone like prohibition and old laws on fugitive slaves, sodomy, investment banking and miscegenation.

Unfortunately, lawmakers sometimes seem to forget they have the power to get rid of a law when it is no longer useful. Somehow, even years later, they appear to convince themselves that they’ve dealt with a pesky issue by passing the old law. It’s as if they put on blinders, likely because they have so many other problems. They forget times and conditions change so much that old solutions need to be reconsidered.

Unfortunately, lawmakers sometimes seem to forget they have the power to get rid of a law when it is no longer useful. Somehow, even years later, they appear to convince themselves that they’ve dealt with a pesky issue by passing the old law. It’s as if they put on blinders, likely because they have so many other problems. They forget times and conditions change so much that old solutions need to be reconsidered.

Such is the case with the Heritage Act, which removed the flag off the dome in 2000 to the Statehouse grounds. But the act went further, creating an African American monument on Statehouse grounds and prohibiting removal of memorials on public property unless there’s a two-thirds vote by the House and Senate.

The last provision is today’s sticky wicket. It meant monuments like those of Confederate soldiers that dot courthouse squares around the state cannot be removed without a state legislative override. In other words, the state gets to decide what happens to monuments on the grounds of local, public parks. Seems a little heavy-handed, no? A way for the state to keep its ham-handed fist on all of those Confederate monuments glorifying the Lost Cause and, many feel, reminding minorities of a generational racial agenda in the Palmetto State?

Some state lawmakers say the Heritage Act is unconstitutional because the two-thirds provision is overly burdensome. Others say it violates home rule. Both are solid points, but there’s a remedy at hand: Fifty percent plus one of the state House and Senate members can vote Wednesday or Thursday to repeal the act. And then it will be over.

Interestingly, the vast majority of South Carolina legislators — 140 of the 170 in the two chambers of the Statehouse — have never had a chance to vote on the Heritage Act, according to an analysis by Statehouse Report. Almost 70 percent of current state senators haven’t had their say. About seven out of eight members of the House haven’t voted on it.

With all of the turmoil in the state, they should have a chance to vote again on the Heritage Act — this time to repeal it. Let’s not kick the can down the road.

Back in 2000 when the Heritage Act was approved, it got a lot of support because lawmakers who never thought the Confederate flag would be removed from the top of the Statehouse dome saw a ray of hope — and understood that the act would get it down. They pounced on the opportunity, figuring they’d deal with the devils in the deal later. Meanwhile, many white conservatives shelved the whole matter, figuring it had been dealt with.

But now come killings by police of unarmed black men from North Charleston to Minneapolis to Atlanta. Now comes the Black Lives Matter movement, which has unwound the festering bandage of racism that boils in our country. Now come protests, unrest and tension in our communities.

The Heritage Act was a remedy for its time. It has been changed once — in 2015, when lawmakers agreed, after the slaughter of S.C. Sen. Clementa Pinckney and eight members of his church in Charleston, to move the battle flag off the Statehouse grounds into a place of history.

That’s where all of these monuments now need to go — away from our public places of honor into a museum or educational setting. Now is the time to repeal the Heritage Act once and for all. It’s time for local communities to have conversations, action and change on how they can start healing decades-old racial wounds and come together as a people.

Carpe diem, state representatives and senators. Deal with the devils in the Heritage Act. Be leaders and help our state to start the healing.

- Andy Brack is editor and publisher of Statehouse Report. Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

Riley Institute at Furman University

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is Furman University’s Riley Institute, which broadens student and community perspectives about issues critical to South Carolina’s progress. It builds and engages present and future leaders, creates and shares data-supported information about the state’s core challenges, and links the leadership body to sustainable solutions.

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is Furman University’s Riley Institute, which broadens student and community perspectives about issues critical to South Carolina’s progress. It builds and engages present and future leaders, creates and shares data-supported information about the state’s core challenges, and links the leadership body to sustainable solutions.

Launched in 1999, the Institute is named for former South Carolina Governor and former United States Secretary of Education Richard W. (Dick) Riley. It is committed to nonpartisanship in all it does and to a rhetoric-free, facts-based approach to change.

- Learn more about the Riley Institute.

- Also learn more about the Riley Institute’s Center for Education Policy and Leadership.

Friends and readers,

We’re proud to offer Statehouse Report for free. For more than a dozen years, we’ve been the go-to place for insightful independent policy and political news and views in the Palmetto State. And we love it as much as you do.

We’re proud to offer Statehouse Report for free. For more than a dozen years, we’ve been the go-to place for insightful independent policy and political news and views in the Palmetto State. And we love it as much as you do.

But now, we can use your help. If you’ve been thinking of contributing to Statehouse Report over the years, now would be a great time to contribute as we deal with the crisis. In advance, thank you.

— Andy Brack, editor and publisher

LEVENTIS: Strong federal oversight is key to fixing policing

By Henry Leventis, special to Statehouse Report | Overcoming racism and acts of brutality by the police requires strong federal oversight. The U.S. Justice Department (DOJ), in particular its Civil Rights Division, was created to protect our constitutional rights, including the right to be free from discrimination and excessive force by police. The recent and tragic deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks and others at the hands of the police remind us why strong federal oversight is needed now more than ever. The DOJ must take the lead in holding everyone, including police officers, equally accountable under the law.

To do so, it must employ all of its resources to identify and root out discriminatory policing and earn the confidence of communities of color. The DOJ has many tools at its disposal, including sections of highly-qualified civil and criminal attorneys focused solely on police misconduct. This expertise is critical when prosecuting police officers because many local prosecutors’ offices are not equipped to handle police brutality cases. Additionally, victims of discriminatory policing will not expect fair treatment from prosecutors who work every day alongside some of the very police departments that violate their rights.

The DOJ also has a Community Relations Service (CRS) meant to build relationships with communities of color before flashpoint events occur. It must prioritize the work of both the Civil Rights Division and CRS and fully empower these groups to do the work they were intended to do.

Regrettably, the current administration’s police oversight efforts are plagued by many avoidable missteps. Former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions severely limited the use of consent decrees — legally enforceable agreements with police departments — that have been successfully used under previous administrations to curb discriminatory policing practices. U.S. Attorney General William Barr has done nothing to change that. This unnecessarily cedes one of the DOJ’s most effective tools for addressing systemic racism in police departments.

At the same time, this administration has not prioritized building relationships with communities of color, hampering its ability to conduct investigations and respond effectively in times of crises. And many of the president’s statements indicate that he has taken sides in the protests over police brutality, making it more difficult for DOJ attorneys to be seen as unbiased.

The administration should reverse course in these areas at once. Further, it should support current legislative proposals requiring police departments to report any use of force to a national database. This would allow the DOJ to use data analytics to quickly identify problem departments and officers and allocate its resources accordingly – an approach that has been wildly successful in other enforcement areas.

This robust approach to federal police oversight would motivate police departments to remove problematic officers before a tragedy occurs. It would provide relief to taxpayers who pay millions of dollars each year to settle police brutality lawsuits. And, most importantly, it would provide communities of color greater confidence that the system works for them. We should demand as much from our federal government, and we should demand it now.

Henry C. Leventis, a Sumter native and 1998 graduate of the College of Charleston, is a former federal prosecutor who handled civil rights cases from 2010 to 2015. He now is in private practice in Nashville, Tenn.

Hooray for Brian Elmore’s call for Medicaid expansion

To the editor:

![]() Hooray for Brian Elmore and the S.C. Hospital Association! Our state has never really looked at the economics of Medicaid expansion.

Hooray for Brian Elmore and the S.C. Hospital Association! Our state has never really looked at the economics of Medicaid expansion.

Every other state that has expanded Medicaid and documented its impact has seen sufficient economic growth to more than compensate any costs that might be incurred by the state. That does not even include direct savings like covering all residents of our state prisons, and lower-income state employees and their children who are currently enrolled in the state’s costly health insurance plan.

— Steve Skardon, Mount Pleasant, S.C.

Column went too far

To the editor:

I am a conservative, white, 68-year-old South Carolinian and I am proud of that. Both my mother and mother-in-law were members of the DAR [Daughters of the American Revolution] and I am proud of that. I am a graduate of Erskine College (before it went off the deep end) with a B.A. in history and I am proud of that. I have only voted for one Democrat in my life but that may very well change with this year’s presidential election.

Your column in this morning’s paper has a lot of good but goes too far with the call to repeal the state’s Heritage Act. First of all, slavery was wrong when the children of Israel were enslaved in Egypt and it is still wrong today and forever. Two of the words that Webster’s Dictionary uses to define heritage are “legacy” and “tradition.” The legacy and tradition of both this state and the nation began over a hundred years before the War Between the States, yes, there is nothing civil about war. The Founding Fathers of this nation and this state owned slaves because it was an economic necessity. Ride by fields of any type today and look at the workers and they do not look like you and me because the economic necessity has not changed. In the 250-year history of this great nation, conditions and opportunities for blacks have certainly improved but they have a long way to go. Those opportunities start with the responsibility of education, not protests.

As you state the great words of Thomas Jefferson, I also firmly believe that all men are created equal. I also firmly believe that the primary goal of the Black Lives Movement is not to change history but to delete it. Taking down statues and not allowing Confederate flags at NASCAR races will not delete history. Repealing the Heritage Act will not delete history. Those actions will not delete the fact that the only birth records that millions of blacks can find are census records that show they were born in slavery. Slavery was wrong but it happened. The goal today should be to live not in the past but despite the past. Live in peace with respect for the person, not for or against the color of one’s skin. “All men are created equal.”

— Andy Sullivan, Honea Path, S.C.

What do you think?

We love hearing from our readers and encourage you to share your opinions. But you’ve got to provide us with contact information so we can verify your letters. Letters to the editor are published weekly. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity. Comments are limited to 250 words or less. Please include your name and contact information.

- Send your letters or comments to: feedback@statehousereport.com

Imposing statue

Here’s an imposing statue located somewhere in South Carolina. But who does it depict, where is it and what’s his story (briefly)? Send your best guess of what it is to feedback@statehousereport.com. And don’t forget to include your name and the town in which you live.

Our previous Mystery Photo

Our June 12 image, “Lots of river rock,” showed the Tamassee DAR School in the extreme northeast tip of the state in Oconee County. Hats off to those who identified the photo: Jay Altman of Columbia; David Lupo of Mount Pleasant; Jacie Godfrey of Florence; and George Graf of Palmyra, Va.

Our June 12 image, “Lots of river rock,” showed the Tamassee DAR School in the extreme northeast tip of the state in Oconee County. Hats off to those who identified the photo: Jay Altman of Columbia; David Lupo of Mount Pleasant; Jacie Godfrey of Florence; and George Graf of Palmyra, Va.

Altman shared this about the school: “ Tamassee DAR School was founded by the Daughters of the American Revolution and opened in 1919. The first class consisted of 23 ‘boarding’ female students. In 1932, the school admitted its first ‘boarding’ male students. In the 1970s the school shifted from a primarily agricultural and industrialized program to serving children in poverty to serving children in crisis. Tamassee transformed from a private boarding school to a children’s home. In March of 2020, the Board of Trustees decided to sunset the residential program, and focus on supplemental education programs for students in Oconee County.”

- Send us a mystery: If you have a photo that you believe will stump readers, send it along (but make sure to tell us what it is because it may stump us too!) Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com and mark it as a photo submission. Thanks.

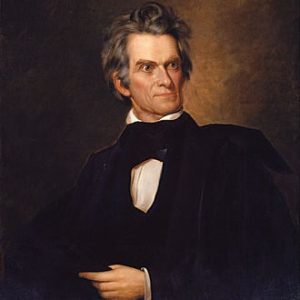

John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun, a former vice president and U.S. senator, was born in Abbeville District on March 18, 1782, the third son of Patrick Calhoun, an upcountry planter and former legislator, and Martha Caldwell. A prodigy, the young Calhoun lost his father at an early age. His older brothers, William and James, already successful cotton planters and merchants, helped finance his education. Calhoun attended rural upcountry academies before entering Yale at age twenty and graduating in two years. He then attended Litchfield Law School in Connecticut before reading law in Charleston with the distinguished attorney William Henry DeSaussure, a prominent Federalist. Calhoun returned to Abbeville and began the practice of law, which he disliked. He quickly turned his attention to politics, winning election to the S.C. House of Representatives in 1808. During his one term as a state legislator, Calhoun supported a white manhood suffrage amendment to the state constitution (adopted in 1810). In 1810 Calhoun ran successfully for Congress as a Jeffersonian Republican and an aggressive champion of national rights in the international arena, thus beginning a long, distinguished, and controversial career in national politics. Before taking his seat in Congress, Calhoun attended to some personal business, marrying his second cousin Floride Bonneau Colhoun on January 8, 1811. The couple eventually had ten children, of whom seven lived to maturity.

During his career Calhoun evolved from “War Hawk” (a faction of Republican congressmen seeking war against Great Britain) nationalist to independent nullifier to strategist for a unified regional (southern) defense of slavery. His winding political odyssey reflected his evolving analysis of the relationship between the nation and its sections. Calhoun insisted that the success of the republican experiment in self government depended not only on the proper distribution of power between the states and the federal government but also on maintaining equilibrium between the sections. In the aftermath of the near-disastrous War of 1812, Calhoun championed a strong nationalist program to increase security and foster commerce across the nation. He sought to “bind the republic together” through tariffs to help infant industry, a second national bank to stabilize the nation’s troubled finances and sustain commerce, and an ambitious system of federally funded internal improvements designed to promote sectional economic interdependence. During his service as secretary of war during the presidency of James Monroe, Calhoun again pursued an aggressive policy to improve military training, education, and engineering; continue transportation improvements; and reduce national reliance on poorly trained state militias in favor of regular troops. In these efforts, his ambitious plans often attracted opposition from economy-minded members of the Monroe cabinet.

Like other members of the Monroe cabinet, Calhoun used his position to advance his presidential ambitions through persuasion and patronage. The North Carolina congressman Bartlett Yancey enviously noted Calhoun’s “talent” for “gaining on strangers” through his power of conversation. At this point in his career, Calhoun drew support chiefly from former Federalists and Republicans with strong nationalist sympathies—people who supported his dream of fostering economic interdependence among sections as a means of strengthening the bonds of union. In the crowded presidential field of 1824, Calhoun’s relative youth worked against him, and the entry of the military hero Andrew Jackson, another South Carolina native whose candidacy triggered a wave of popular enthusiasm not previously seen in American politics, doomed his chances. Thus, Calhoun withdrew from the race and sought the vice presidency, which he won easily. As vice president, however, Calhoun quickly broke with new president John Quincy Adams when the Massachusetts native insisted on appointing Speaker of the House Henry Clay as secretary of state. Calhoun believed that Adams’s choice of the wily Kentuckian for the key cabinet slot gave credence to Jackson’s charge that a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Clay had denied the presidency to the old “Hero of New Orleans,” who had won the popular vote. Calhoun quickly emerged as a key figure in the pro-Jackson opposition to the Adams administration.

Despite his prominence in the emerging Jackson coalition, and his easy reelection as vice president on the Jackson ticket in 1828, Calhoun’s youthful nationalism had waned by the late 1820s, falling victim to the emergence of a persistent factional majority favoring protective tariffs. Calhoun, along with many other southerners, judged these tariffs as unfair to the South and harmful to the southern staple economy. The South Carolinian now feared the centrifugal pull of divergent sectional forces less than he did the gradual consolidation of power in the hands of the national government. To stop this steady accretion of federal power, to relieve the slaveholding South from the economic burden of the tariff, and to guard against possible federal interference with slavery at some future date, Calhoun developed the idea of nullification. Nullification, as Calhoun fashioned it, was a constitutional mechanism that allowed an individual state, falling back on its claim to original sovereignty, to suspend operation of a federal law it deemed unconstitutional, unless or until three-fourths of the states decided otherwise.

Inside South Carolina the nullification campaign mobilized the Palmetto electorate as never before, and the canvass for election of delegates to the special convention turned the state into “a great talking and eating machine” as courthouse debates and political barbecues became the order of the day. This campaign generated high levels of voter turnout across the state. But the hotly contested nullification battle, which the nullifiers won with roughly sixty percent of the popular vote, left the state bitterly divided and with armed conflict looming in some districts, forcing Calhoun into the role of peacemaker, which he fulfilled skillfully. Outside of South Carolina, the doctrine of nullification attracted less support than Calhoun and his allies expected. Nullification suffered political defeat when President Jackson discredited the movement politically by equating it with disunion and isolating Calhoun from the southern wing of the emerging Democratic Party.

With the political failure of nullification, Calhoun gradually emerged as the leading strategist of an evolving southern sectionalism. Only a united South, Calhoun repeatedly maintained over the final decade of his life, could protect its rights (especially the right to hold slaves) within the Union. A united South, acting in concert and transcending partisan divisions, Calhoun claimed, could readily defend the region’s slaveholding society against threats from a northern majority increasingly hostile toward slavery. Near the end of his life, Calhoun feared that the too-powerful national government would fall into the hands of an antislavery majority. “I am a Southern man and a slaveholder . . . I would rather meet with any extremity upon earth than give up one inch of our equality,” Calhoun told the Senate in 1847. His remedy centered on the maintenance of sectional political equilibrium within the Union through the adoption of a constitutional amendment allowing a sectional minority to veto federal legislation. Calhoun failed to unite the South behind his ideas, however, because most southerners thought that slavery was best defended through continued southern influence on national parties. With partisan differences still dividing the South internally, and the controversy over the expansion of slavery in full flower, Calhoun died on March 31, 1850, in Washington from respiratory complications related to tuberculosis. In April he was buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard in Charleston.

In life, Calhoun was hardly the brooding and forbidding figure portrayed in later mythology. In 1829, when the Beaufort planter and scholar William Elliott first met Calhoun, he called the vice president “a very eloquent and imposing man in his conversation— and a most subtle politician.” Throughout a turbulent political career, Calhoun proved a loving and even indulgent father, who sacrificed financially to advance his sons and who maintained a close and intellectually stimulating relationship with his daughter Anna Maria Calhoun Clemson, who followed politics closely and became an engaging correspondent. He was also a devoted and dutiful husband to a wife who grew more withdrawn and difficult with age. An energetic political correspondent to a large network of friends, allies, and political contacts and an accomplished cotton planter, Calhoun enjoyed time at his Fort Hill plantation in the far upcountry of South Carolina (later the site of Clemson University). But neither Calhoun’s family and friends nor his plantation engaged his energies as much as politics did. A man of considerable intellectual gifts, Calhoun maintained a focus on politics throughout his adult life. His political ambition, and particularly his presidential aspirations, drew sharp and frequent criticism from his opponents. But for the most part, people who knew Calhoun well, including some of his most determined opponents in South Carolina, admired his prodigious ability and conceded his capacity for magnanimity and compromise.

Calhoun’s chief contribution to American political thought consisted of his thoughtful reconsideration of the republican wisdom received from the founders. The founders had embraced Madison’s theory of extended republics to solve the problem of majoritarian tyranny in a democratic republic. Madison argued that the multiplicity of factions included in a large republic, and the geographic distance separating them, would render the formation of a durable and oppressive majority impossible. As plausible as this argument seemed in the 1780s, Calhoun recognized that the rise of partisan politics left it outmoded by the 1840s. Political parties, taking advantage of transportation and communication improvements and using expanding federal patronage aggressively, had easily overcome the barriers of distance and diversity that Madison believed would block the formation of lasting majorities.

In his major speeches and writings of the nullification era and with the posthumous publication of his two systematic political treatises, A Disquisition on Government and A Discourse on the Constitution of the United States, Calhoun found a check on majority power in giving significant minority interests veto power. He maintained that the appropriate expression of a society’s political will came not through the opinion of a numerical majority, but through the consensus that emerged when all of the community’s component interests were consulted. Calhoun sought a government by supramajority, a consensus reached by obtaining the common consent of the society’s conflicting interests. He called this calculus of consent government by the concurrent majority. In Calhoun’s mind, the power of the concurrent majority, when given an adequate instrument of its expression (for example, nullification, sectional veto), could serve as a check on the power of renegade numerical majorities. In an era of democracy, Calhoun sought to check the power of one kind of majority (numerical) with that of another (concurrent).

Rooted in his admitted desire to protect slavery in the American South, Calhoun’s theoretical positions were often dismissed by critics as special pleading. The differing interests protected in Calhoun’s ideas were sectional, and it was unclear how minority interests within sections would be protected. The consensus and harmony that Calhoun thought government by concurrent majority would produce seemed likely to prove illusory, with stalemate and paralysis their likely surrogates. To Americans enamored by the expansion of democracy (at least for white males) and opportunity (for free Americans) during the so-called Age of Jackson, Calhoun’s government by concurrent majority seemed an anachronism, a strangely anti-majoritarian project in a fiercely majoritarian age. But if Calhoun’s remedy seemed conservative and impractical, his indictment of the excesses of majority rule, and his exposition of a conservative, post-Madisonian republicanism that highlighted the obsolescence of much of the founders’ logic, earned him a deserved reputation as one of nineteenth-century America’s foremost political thinkers. The problem that Calhoun identified and grappled with throughout his career—the difficulty of protecting the rights of political minorities against the power of elected majorities—remains one of the most vexing dilemmas of modern democracy. For all of his flaws, and the tragedy involved in the employment of his vast talents in defense of racial slavery, Calhoun still stands as second only to James Madison as an original political thinker among practicing politicians in American life.

— From an entry by Lacy Ford. This entry may not have been updated since 2006. To read more about this or 2,000 other entries about South Carolina, check out The South Carolina Encyclopedia, published in 2006 by USC Press. (Information used by permission.)

ABOUT STATEHOUSE REPORT

Statehouse Report, founded in 2001 as a weekly legislative forecast that informs readers about what is going to happen in South Carolina politics and policy, is provided to you at no charge every Friday.

Meet our team

- Editor and publisher: Andy Brack, 843.670.3996

- Statehouse correspondent: Lindsay Street

Buy the book

Now you can get a copy of editor and publisher Andy Brack’s We Can Do Better, South Carolina! ($14.99) as a paperback or as a Kindle book ($7.99). . The book of essays offers incisive commentaries by editor and publisher Andy Brack on the American South, the common good, vexing problems for the Palmetto State and interesting South Carolina leaders.

More

-

- Mailing address: Send inquiries by mail to: 1316 Rutledge Ave., Charleston, SC 29403

- Subscriptions are free: Click to subscribe.

- We hope you’ll keep receiving the great news and information from Statehouse Report, but if you need to unsubscribe, go to the bottom of the weekly email issue and follow the instructions.

- Read our sister publications: Charleston City Paper (every Wednesday) | Charleston Currents (every Monday).

- © 2020, Statehouse Report, a publication of City Paper Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.