By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | As South Carolina charts a path out of the pandemic, here are some ideas from conversations with 10 people from the black, Hispanic and Native American communities for building a more resilient South Carolina.

Expanding access to health care

Gaining equal access to health care was a key concern for many.

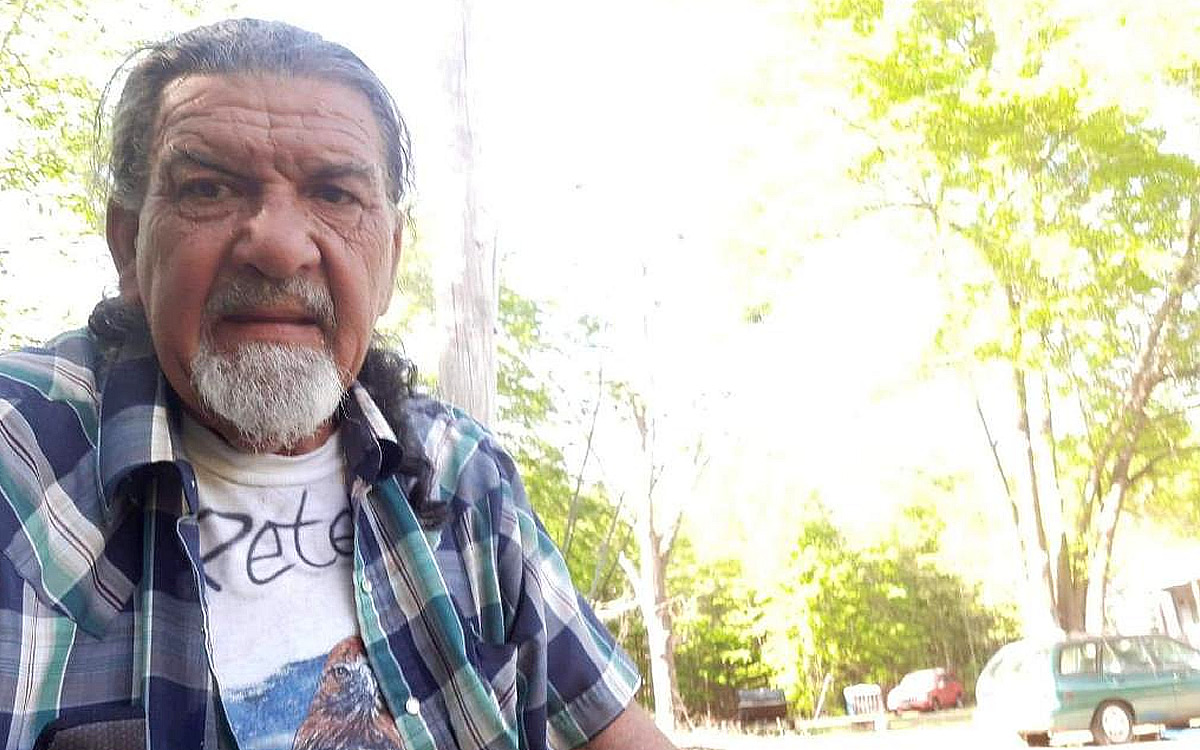

Pee Dee Indian Tribe Chief Pete Parr of Marlboro County said the lack of a hospital in Bennettsville creates a hardship on his people and the surrounding community.

“A hospital is very important for our community and our tribe and by not having a hospital here in the Bennettsville area, it has put our people in a predicament,” he said. Rural hospital closures have been a problem in South Carolina and the nation.

Some said the state should reevaluate expanding Medicaid, an option the state has declined since 2009. Some of the states that initially declined Medicaid expansion have since expanded the federally supported service to include more people.

“The need right now, more than ever, is to expand Medicaid,” North Charleston Democratic Rep. J.A. Moore said. “Now is a time to not play politics and expand Medicaid so we can really ensure people can have the health care coverage we need.”

In addition to expanding Medicaid, Moore said state lawmakers need to do better in funding the state departments that focus on health, environment and mental health.

Journalist Fernando Soto of Charleston said people who are not insured also have difficulty in obtaining coronavirus tests. For that reason, he said, there should be skepticism when looking at S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control’s demographic data for COVID-19, which lists 5 percent of cases as Hispanic.

“That’s very concerning because that number seems very minute,” he said. “To this day, I don’t know where anybody would go for a free test. Hispanics, by and large, have to pay for things out of pocket because they don’t have health care coverage.”

Improving education

Education for adults and children was a recurring theme.

“It takes upfront investment in our citizens. I don’t think we can commit to long-term resiliency in South Carolina without investing in how we educate our kids,” Moore said.

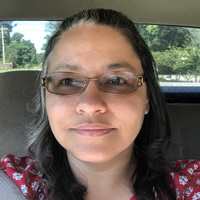

University of South Carolina SNAP-Ed coordinator Ashley Page of Columbia said it was ironic the legislature spent two years debating paying teachers more “and then the middle of March happened.”

“Now folks have really started to understand what teachers are going through,” she said.

S.C. Association of Community Economic Development CEO Bernie Mazyck of Summerville said South Carolina needs to rally around teachers post-pandemic.

“One of the things that’s clear from this pandemic and this shelter-in-place order that we are currently living under everyone will say teachers are gold, and as such we should pay them as the gold that they are. The General Assembly has to be forced to increase the budget for teacher pay,” he said.

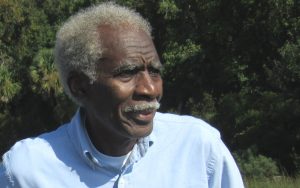

For Dr. Emory Campbell of Hilton Head Island, education needs to extend beyond traditional education, especially for minority communities.

“We strengthen them by sharing the history with them or reteaching. Allowing families to begin to learn their history and their culture and that’s how you strengthen the community, empower the community to do what they do best,” Campbell said. “The rural communities in South Carolina and the communities along the coast, what they need most is education and how-to programs.”

Campbell, retired as leader of the Penn Center on St. Helena Island,said those how-to programs should teach everything from gardening to finances. Born into the Gullah community of Hilton Head, Campbell said the community is made more vulnerable now by loss of identity and loss of skills.

“We dragged them off to work, we educated them poorly and yet they’re the ones that had the resources to develop themselves,” he said.

For some, better education came down to access to the internet.

Parr said that as the state shifted public education to online, some children in his community “have not had a lesson since they left the school house” despite the district’s attempt to provide wi-fi from buses. He said it will put his community further behind.

Soto said the immigrant community is facing a different challenge: parents are out working and cannot help children with school work, and sometimes the parents don’t speak the language or have enough education to help.

Raising the minimum wage, affordable housing

Page said she is hopeful the state government leaders will see that the minimum wage in South Carolina — $7.25 an hour, which equates to $15,080 annually at 40 hours a week — “is not enough.”

North Charleston Democratic Rep. Marvin Pendarvis echoed that comment.

“So many people in vulnerable communities, they work 9 to 5, they work minimum wage, and that’s not enough for them to take care of their children and pay rent and utilities,” he said, adding it also speaks to an affordable housing issue in the state. Both lead to financial instability for the most vulnerable, he said.

Mazyck said the pandemic has shown who the most essential and yet most underpaid workers are in the state.

“When you look at the bus drive, the Uber driver, the restaurant server, the fast food server, when you look at all of those professions the health professionals up and down the professional ranks, we now see how important those people are to our quality of life and to our economy but they’re the ones paid the least, paid on an hourly basis,” he said. “Then in order for them to live, housing is unaffordable so they oftentimes are living in substandard housing.”

Building financial preparedness

Parr of Marlboro County said his community was ill-prepared for the pandemic. Pantries are sparse in normal times and during the time of crisis, many were unable to attain the goods they needed like toilet paper, he said.

Mazyck said crises sometimes lead to low-income workers borrowing from high-interest payday or title loan lenders, a stopgap that could further undermine their financial situation.

“Those types of lenders, in a lot of cases, are predatory. They don’t build or help that customer to help them get out of that loan or build that credit rating,” he said. “As a result they fall further and further into economic dismay so we need financial systems that work so folk can access them. Some of that might require more financial education, credit counseling.”

Page said she’d like to see more support for women and minority entrepreneurs as the state moves out of the crisis.

Former GOP S.C. Rep. Samuel Rivers, who is challenging Moore for his former seat in November, said financial preparedness of the individual will help people weather storms like this better.

“People need to be a little more financially prepared for times like these,” he said. He said financial preparedness and helping some South Carolinians get out of “the renting stage” will help people become more self-reliant.

Building resiliency through faith

Sabrina Grey Wolf Creel of Walterboro, a tribal council board member for the Edisto Natchez-Kusso Tribe, said that she’s noticed a bright spot from the pandemic: People are spending more time with family and with God.

“The pandemic took away shopping, sports events and all these things,” she said. “It made you put back into focus the things that really matter like your family, your household, and making sure your neighbor is well taken care of as well. It’s almost like a pause in time to see where you really are.”

She said she hoped people will continue with a new perspective moving forward.

“For us to go stronger, it’s putting God back in the center of it and move forward,” Creel said. “Love your neighbor as you love yourself.”

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

Pingback: Charleston Currents – New for 4/27: On finances, doubletalk, concert, Provence