Mine was called the “Liar’s Tour.” The dozen people in the group were told that everything they heard on the tour was true – except for one thing. Their job was to figure out the lie.

Mine was called the “Liar’s Tour.” The dozen people in the group were told that everything they heard on the tour was true – except for one thing. Their job was to figure out the lie.

So they heard about the Big Brick, a high-end brothel on Fulton Street that now is a fancy restaurant. They learned about the fire that destroyed a Catholic cathedral in 1861, an inn that was home to a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the Four Corners of Law and the nation’s oldest theater.

They walked by a brick-walled graveyard dripping with Spanish moss. “In the back is where the last lynching in Charleston took place back around 1903. That was called the lynching tree.”

No one ever guessed the tall tale was the so-called lynching tree. Instead, they guessed the lie to be about the house of ill repute or an artist’s studio or something else.

This is a sad story because it illustrates how visitors were all too ready to believe a lynching took place in a sacred church cemetery. Their preconceptions about South Carolina made them accept a fake lynching story.

And that’s one reason why South Carolina – and the American South – needs to confront its history of racially-motivated terror and lynching. If statues to the Confederate dead are going to continue to loom over public properties across the South as a reminder of the Lost Cause and white supremacy, then local governments and organizations need to erect historical markers to give the context of the environment of fear created for generations in the Jim Crow era.

“Racial terror lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials,” according to the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala. “Lynchings in the American South were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynching was targeted racial violence at the core of a systematic campaign of terror perpetuated in furtherance of an unjust social order.”

“Racial terror lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials,” according to the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala. “Lynchings in the American South were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynching was targeted racial violence at the core of a systematic campaign of terror perpetuated in furtherance of an unjust social order.”

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has done extensive research to tell the story of more than 4,000 documented racial terror lynchings in the South after Reconstruction, from 1877 to 1950. Earlier this year, EJI opened a national memorial and a museum to inform people about the legacy of lynching.

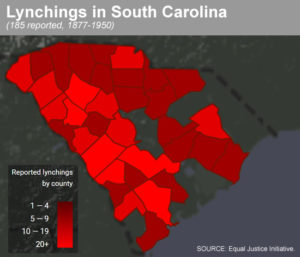

EJI documented at least 185 cases of lynchings across South Carolina. It’s fewer than the number of lynchings recorded in other Deep South states. Nevertheless, South Carolina was a violent place after Reconstruction. By 1890, historian Walter Edgar writes “the state had three times as many murders as did all the New England states combined (with a population four times as large.) The white minority, not the black majority, was responsible for the largest share of the killings. And as often as not their victims were fellow whites.”

In some South Carolina counties, such as Charleston, Richland and Horry, EJI currently doesn’t have any recorded racial terror lynchings. That doesn’t mean there wasn’t a real lynching tree somewhere in any of those counties. It just means researchers haven’t yet confirmed any racial terror deaths in those places.

“With regards to Charleston, there are many victims who fall outside the parameters of our research due to date of death or number of documenting sources,” said EJI’s Jonathan Kubakundimana. “We primarily included individuals whose murders we could document with two or more primary sources.

“Our work is ongoing and evolving and we are continuing to learn about victims who do fall within our research parameters.”

South Carolina’s last lynching came in 1947 in Pickens County with the death of Willie Earle, charged with the murder of a Greenville cab driver. Gov. Strom Thurmond urged vigorous prosecution of 31 people arrested, but all were acquitted by a jury. Three years later, a young state representative, Fritz Hollings, authored a tough anti-lynching law signed by Thurmond that set the death penalty for lynching. They stopped.

Lynchings are a grisly part of our history. Counties should work with EJI so we never forget what happened.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.