NEWS: Data hub for education, workforce could be saved, proponents say

NEWS BRIEFS: From the car cluster to the end of snow days … and more

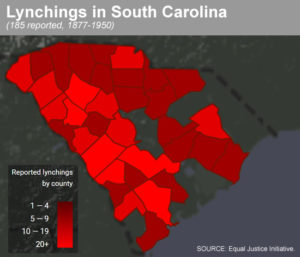

COMMENTARY, Brack: Markers needed to remember victims of S.C. lynchings

SPOTLIGHT: S.C. Senate Democratic Caucus

FEEDBACK: On nuclear waste, elections and Trump

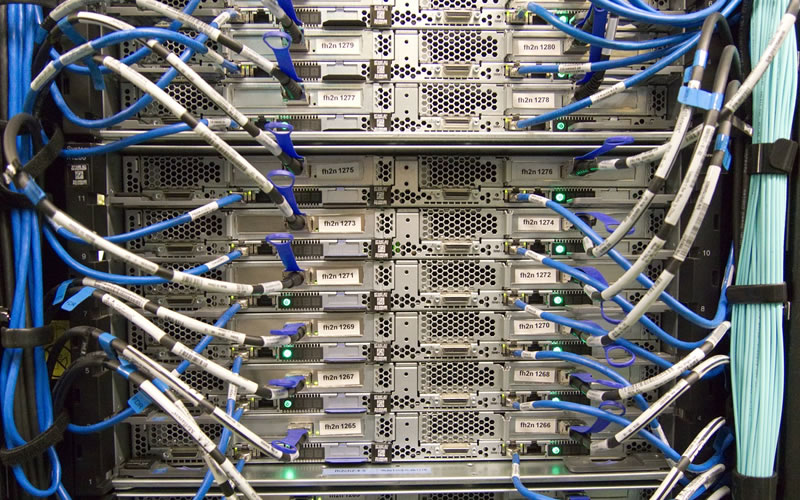

MYSTERY PHOTO: Another extreme close-up

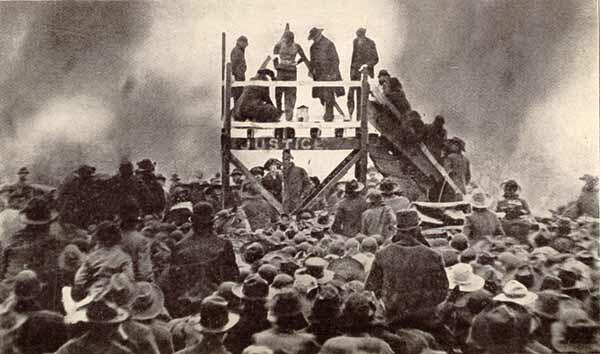

S.C. ENCYCLOPEDIA: Lynching in South Carolina

NEWSNEWS: Data hub for education, workforce could be saved, proponents say

By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | State officials and a key lawmaker say it may not be too late to rescue a proposed state data warehouse to collect, store and access data on South Carolina students from kindergarten into their employment years. But for now, privacy concerns have shelved the plan.

The warehouse sought to create a single digital hub where multiple state agencies would contribute data on South Carolina citizens, everything from third-grade reading evaluations to driving records. In turn, agencies using the warehouse and others could access data to assess value and efficiency of the state’s education system in terms of workforce readiness.

Gov. Henry McMaster vetoed a budget proviso establishing the warehouse on July 5. But he called the idea “meritorious.”

“South Carolina’s workforce requirements are urgent and ongoing, and I thank the General Assembly for endeavoring to resolve the problem,” McMaster wrote in his veto message. But he wanted lawmakers to go “back to the drawing board” over privacy concerns.

If lawmakers don’t override McMaster’s veto, then legislation is imminent when session begins in January, S.C. House Ways and Means Committee Chair Brian White, R-Anderson, told Statehouse Report.

“The data warehouse would give South Carolina’s workforce pipeline stakeholders another tool in the arsenal to address critical workforce needs,” White said. “You got to have the data if you’re spending the money doing the training. You got to make sure we’re getting the outcomes with the public money.”

Background

The 2018-19 budget proviso was inserted by White after two years of work by about 20 state agencies.

Under the S.C. Department of Commerce, the S.C. Coordinating Council for Workforce Development (CCWD) began a Data Sharing Committee that has met since November 2016. The latest meeting was June 26.

According to documents obtained by Statehouse Report, agencies with representatives at meetings included the state departments of Commerce, Administration, Education, Revenue, Transportation, Employment and Workforce, Motor Vehicles, and Health and Environmental Control, as well as the state Education Oversight Committee,, Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office, S.C. First Steps, the Commission on Higher Education, the S.C. Technical College System, multiple universities, the S.C. Power Team, the S.C. Labor, Licensing and Review, and Able SC.

Elisabeth Kovacs, who oversees CCWD as Commerce’s deputy director of workforce development, described the proviso as “a branch to get us going on the process” and that it was

“only intended to be a bridge, and the coordinating council (created in the proviso) will review the legislation and recommend it for next session.”

‘A real star’

South Carolina’s effort to create a workforce data warehouse is part of a national trend focused on using data sharing for workforce development. Under then-Gov. Mike Pence, Indiana was one of the first in the nation to create an accessible database that aligns education goals with workforce development. Now, the Trump administration has made workforce development a key mantra, such as when President Donald Trump visited Boeing South Carolina’s plant earlier this month.

South Carolina was one of five states working with the national nonprofit Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness (CREC) on creating education-and-workforce databases.

“There is a movement afoot of promoting evidence based policy at the national level,” CREC CEO Ken Poole told Statehouse Report.

Center officials said South Carolina offered “the most ambitious plan.”

“South Carolina was a real star in our effort,” CREC senior research fellow Marty Romitti said. “South Carolina had a lot of assets in place.”

Those assets included a legislative mandate to compile a list of workforce development programs and an existing, 15-year-old data warehouse. Housed under the S.C. Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office (RFA), the existing digital warehouse holds medical information that is accessible by multiple state agencies.

“We were in an advantage because the infrastructure is already here,” Kovacs said. She added that also meant zero-cost to taxpayers in the proviso.

The state’s existing data warehouse was created in the 2002-03 budget to provide support to state departments of Health and Human Services, and Social Services and other agencies as needed, according to the RFA. Like the proposed education-workforce database, the health database does not contain any new information, but offers an easier way of accessing the information.

This month, the RFA gained recognition from the National Governors Association for maintaining “an integrated data system” that offers a “promising example” of data use.

Privacy concerns

The new data warehouse proviso cleared the House and Senate with no debate. But a week prior to McMaster’s veto of the proviso, the S.C. Policy Council brought the data warehouse to light in its publication The Nerve.

The proviso set off alarm bells for SCPC President Ashley Landess for two reasons. First were the privacy concerns outlined by McMaster and the potential for hacking. And second, Landess questioned whether S.C. public education should be “catering” to the needs of private industry, bucking a trend among politicians and bureaucrats seeking to better align public education with workforce needs. Landess also added that the warehouse could spell the beginning of tracking individual citizens.

McMaster summed up concerns about the warehouse in this statement:

“Under this provision state agencies would be required to turn over the personal information of South Carolina citizens for any reason or no reason at all. This proviso provides no official oversight for the decisions made by the data warehouse committee, no requirement that citizens consent to their personal information being released and quite frankly no one to say ‘no’ or ‘pull the plug’ before it’s too late.”

Privacy professor Allyson Haynes Stuart of the Charleston School of Law said concerns over data sharing systems and individual privacy were to be expected.

“They’re supposed to track people kindergarten through the workforce and, not surprisingly, they have raised a lot of red flags,” she told Statehouse Report. “There’s no limitation on the types of information that is gathered here.”

And that data can be shared with multiple agencies, exposing it to hacking weaknesses, but also with no clear limitation on who can access the data, Stuart said.

Kovacs said that the agencies worked very carefully with attorneys and economists to word the proviso, keeping in mind that sensitive data is being housed there. She said that while there were no outside privacy experts consulted for drafting the proviso, there were state agencies’ personnel who are privacy officers or data management personnel.

Moving forward

Stuart said the proviso needs work and lawmakers should consider the following for drafting legislation to make privacy stronger:

- Be more specific about the purposes for gathering the data and how the data is obtained;

- Outline exactly who can access the information;

- Codify a regular audit; and,

- Allow individuals to see what information is collected about them.

Still, Stuart called the warehouse a good idea.

“They want to improve student outcomes and make sure South Carolina is competitive in the education and workforce field, and that is a laudable goal but we need to make sure in fulfilling that goal we don’t take steps that will violate privacy and cause even more damage,” she said.

But Landess said no amount of privacy-protection promises would make the warehouse a good idea.

“It’s a bunch of politicians and well-meaning bureaucrats that have decided they need to take control of education and make sure these children get a job,” she said.

White said he “would hope so” that his fellow lawmakers would overturn the veto, which could happen as soon as September when General Assembly leaders have said they will address budget vetoes.

“We talked to some of them. It obviously passed in the budget on the floor, so I think a lot of us out there already understand it,” White said. “Without access to these data, it will be much more difficult to ensure that education and training programs are delivering the skills necessary to fill current and anticipated needs.”

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

BRIEFS: From the car cluster to the end of snow days … and more

By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | South Carolina uses a winning strategy among its peers when it comes to driving the automobile industry into the state, according to a new report through the Brookings Institute.

The case study on Upstate South Carolina, “Rethinking Clusters Initiatives, highlights how South Carolina focused on creating automotive engineering talent through public education and encouraged industry-relevant research at its public institutions. An excerpt:

“Business attraction-led cluster development is a somewhat risky strategy—as many bets on individual firms end up failing—but South Carolina’s decision has paid off because of local and state investments in workforce training, supplier development, applied research, transportation and logistics infrastructure, and smart branding and promotion that have helped sustain and grow the automotive cluster over time.”

Other recent news:

Goodbye, snow days. An Upstate school district has become the first in the state to implement a new online learning program to eliminate inclement weather days. Anderson County School District 5 will make use of its Chromebook program and require students to attend online class when weather makes it too dangerous for them to physically attend school. Read more.

Education gaps between races in S.C. The Charleston area’s education system widely favors its white population, according to a new report released by WalletHub. The report looks at how well educated citizens are of top metropolitan areas, but also highlighted racial and gender gaps. Charleston ranked 115th and Columbia ranked 130th for quality of education and attainment gap, a metric that included quality of public schools, quality of public universities, summer learning opportunities per capita, gender education gap, and racial education gap. Myrtle Beach ranked 14th and Greenville ranked 77th. Read the report here.

Winning on wine. South Carolina has the 18th highest wine taxes in the nation at $1.08 per gallon, according to a new report from Tax Foundation. But pop the cork and celebrate that you’re not in Kentucky, where the state levies $3.47 per gallon. The lowest rates are found in California and Texas at $0.20 per gallon. Read the report here.

Precinct-by-precinct look at 2016 election. By now we’ve all seen which congressional districts were red and blue in the 2016 election, but The New York Times is offering a more detailed look. The map goes precinct-by-precinct, showing how voters cast ballots in the 2016 presidential election. Click here to see the map.

COMMENTARYBRACK: Markers needed to remember victims of S.C. lynchings

Mine was called the “Liar’s Tour.” The dozen people in the group were told that everything they heard on the tour was true – except for one thing. Their job was to figure out the lie.

Mine was called the “Liar’s Tour.” The dozen people in the group were told that everything they heard on the tour was true – except for one thing. Their job was to figure out the lie.

So they heard about the Big Brick, a high-end brothel on Fulton Street that now is a fancy restaurant. They learned about the fire that destroyed a Catholic cathedral in 1861, an inn that was home to a signer of the Declaration of Independence, the Four Corners of Law and the nation’s oldest theater.

They walked by a brick-walled graveyard dripping with Spanish moss. “In the back is where the last lynching in Charleston took place back around 1903. That was called the lynching tree.”

No one ever guessed the tall tale was the so-called lynching tree. Instead, they guessed the lie to be about the house of ill repute or an artist’s studio or something else.

This is a sad story because it illustrates how visitors were all too ready to believe a lynching took place in a sacred church cemetery. Their preconceptions about South Carolina made them accept a fake lynching story.

And that’s one reason why South Carolina – and the American South – needs to confront its history of racially-motivated terror and lynching. If statues to the Confederate dead are going to continue to loom over public properties across the South as a reminder of the Lost Cause and white supremacy, then local governments and organizations need to erect historical markers to give the context of the environment of fear created for generations in the Jim Crow era.

“Racial terror lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials,” according to the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala. “Lynchings in the American South were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynching was targeted racial violence at the core of a systematic campaign of terror perpetuated in furtherance of an unjust social order.”

“Racial terror lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials,” according to the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala. “Lynchings in the American South were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynching was targeted racial violence at the core of a systematic campaign of terror perpetuated in furtherance of an unjust social order.”

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has done extensive research to tell the story of more than 4,000 documented racial terror lynchings in the South after Reconstruction, from 1877 to 1950. Earlier this year, EJI opened a national memorial and a museum to inform people about the legacy of lynching.

EJI documented at least 185 cases of lynchings across South Carolina. It’s fewer than the number of lynchings recorded in other Deep South states. Nevertheless, South Carolina was a violent place after Reconstruction. By 1890, historian Walter Edgar writes “the state had three times as many murders as did all the New England states combined (with a population four times as large.) The white minority, not the black majority, was responsible for the largest share of the killings. And as often as not their victims were fellow whites.”

In some South Carolina counties, such as Charleston, Richland and Horry, EJI currently doesn’t have any recorded racial terror lynchings. That doesn’t mean there wasn’t a real lynching tree somewhere in any of those counties. It just means researchers haven’t yet confirmed any racial terror deaths in those places.

“With regards to Charleston, there are many victims who fall outside the parameters of our research due to date of death or number of documenting sources,” said EJI’s Jonathan Kubakundimana. “We primarily included individuals whose murders we could document with two or more primary sources.

“Our work is ongoing and evolving and we are continuing to learn about victims who do fall within our research parameters.”

South Carolina’s last lynching came in 1947 in Pickens County with the death of Willie Earle, charged with the murder of a Greenville cab driver. Gov. Strom Thurmond urged vigorous prosecution of 31 people arrested, but all were acquitted by a jury. Three years later, a young state representative, Fritz Hollings, authored a tough anti-lynching law signed by Thurmond that set the death penalty for lynching. They stopped.

Lynchings are a grisly part of our history. Counties should work with EJI so we never forget what happened.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

SPOTLIGHT: S.C. Senate Democratic Caucus

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is the S.C. Senate Democratic Caucus. Organized more than 25 years ago, the Caucus has played an important role in many of the historic issues facing our state. As a vibrant minority party in the Senate, its role is to represent our constituents and present viable alternatives on critical issues. The S.C. Senate Democratic Caucus remains a unique place for this to occur in our policy process.

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is the S.C. Senate Democratic Caucus. Organized more than 25 years ago, the Caucus has played an important role in many of the historic issues facing our state. As a vibrant minority party in the Senate, its role is to represent our constituents and present viable alternatives on critical issues. The S.C. Senate Democratic Caucus remains a unique place for this to occur in our policy process.

- Learn more about the Caucus at: scsenatedems.org.

FEEDBACK: On nuclear waste, elections and Trump

Turn nuclear waste into glass, not MOX fuel

Turn nuclear waste into glass, not MOX fuel

To the editor:

Mr. Echols [My Turn, 7/20] fails to provide information regarding the pitfalls of MOX. MOX is riskier than standard fuel and there are better ways to dispose of excess plutonium.

In a 2011 article in Scientific American, ” … Edwin Lyman, senior scientist for global security at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington, D.C., argues that MOX is more likely to cause nuclear accidents than ordinary uranium fuel and is liable to release more harmful material in the event of an accident. “Plutonium has different properties than uranium 235 that generally tend to degrade some of the safety systems in nuclear plants,” Lyman says. For instance, because weapons-grade plutonium fissions more readily than uranium 235, reactors may need more robust control rods—neutron absorbers that shut down the nuclear chain reaction when inserted into a reactor’s core. “You never get quite as much margin even after doing all that as you do with uranium,” Lyman says.

The bottom line issue is that utility plants are not willing to use MOX. Why would any utility want to use such dangerous material?

Turning the waste into glass is much safer and would alleviate some of the concerns about burial leakage. Nuclear waste is such a hazardous material [that] our public officials, like Mr. Echols, should be advocating for the least harmful method of dealing with it.

— Cassandra Fralix, Lexington, S.C.

Republicans need to step up on elections

To the editor:

I’m concerned that few Republicans care that our election process — upon which our entire country’s history and future are based — was (and continues to be, according to top-level U.S. security officials) jeopardized by Russia.

This isn’t entertainment news nor is it someone’s crackpot theory meant to rile up the masses; this happened and is continuing to happen. Unless Republicans mean to align themselves with an authoritarian White House that openly approves of international tyrants and repressive regimes, they need to step up and do something. Individuals currently in power must realize that authoritarianism will harm even them and their loved ones. This should not be a partisan matter.

— Meredith Sterling, West Columbia, S.C.

Believes Trump is apolitical

To the editor:

It was [President} Obama who said “elections have consequences” and in [President} Trump’s case, the consequences are outstanding!

Please stop whining and embrace an apolitical leader for a chance. [Special Counsel Robert] Mueller and the collusion myth is total bullshit that’s all the left has to offer!

— Lou Hethington, Charleston, S.C.

Send us your thoughts. We love hearing from our readers and encourage you to share your opinions. But you’ve got to provide us with contact information so we can verify your letters. Letters to the editor are published weekly. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity. Comments are limited to 250 words or less. Please include your name and contact information.

- Send your letters or comments to: feedback@statehousereport.com

MYSTERY PHOTO: Another extreme close-up

Since last week’s close-up mystery was perplexing to so many readers, we thought we’d give you another similar photo this week. If you live in Charleston (hint, hint), you’ve probably seen this place before. So what is it? Send your guess to: feedback@statehousereport.com. And don’t forget to include your name and the town in which you live.

Our previous Mystery Photo

Our July 20 mystery was tough, especially for anyone who had not physically seen the intricate brickwork of the building. The image, provided by photographer Bill Segars of Hartsville, was a close-up of the old Anderson County courthouse in Anderson.

Our July 20 mystery was tough, especially for anyone who had not physically seen the intricate brickwork of the building. The image, provided by photographer Bill Segars of Hartsville, was a close-up of the old Anderson County courthouse in Anderson.

State Public Service Commissioner Tom Ervin of Greenville, a former state circuit judge, remembers well the building. It’s “not to be confused with the new Anderson County Courthouse (circa 1999) across the square,” he wrote in a note identifying the Mystery Photo. “The he historic courthouse was built using architectural plans from Washington County, Georgia, as the Anderson County commissioners liked it and also wanted to save taxpayers some money. The original version had turrets on the four corners which were later removed. The old courthouse now hosts county council chambers in what was formerly the courtroom and administrative county offices.”

Hats off to two more photo sleuths who identified the courthouse: Faith Line of Anderson and George Graf of Palmyra, Va.

Graf said the photo posed a difficult challenge and provided more background: “According to courthouses.co, Anderson County is named for Robert Anderson, who was a soldier in the American Revolutionary War. The old courthouse was built in 1896-1897. The architect was Frank Pierce Milburn who according to Wikipedia was also the architect for many other government buildings and courthouses. Some of these include the City Hall and Theater for both Darlington and Columbia, the Statehouse dome, the designs for Charleston’s City Hall and the Governor’s Columbia mansion, Gibbes Museum of Art, Union Station in Columbia, Southern Railway Stations in Summerville and Aiken, and the Newberry Courthouse.”

- Send us a mystery: If you have a photo that you believe will stump readers, send it along (but make sure to tell us what it is because it may stump us too!) Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com and mark it as a photo submission. Thanks.

HISTORY: Lynching in South Carolina

S.C. Encyclopedia | The origin of the word “lynching” has several explanations. The most common account has it derived from Charles Lynch, a justice of the peace in Virginia, who excessively punished Loyalists during the Revolutionary War. Thus, extreme punishment became known as “Lynch Law.”

Another explanation, from the Oxford English Dictionary, suggests that the term derives from Lynches Creek, South Carolina. By 1768, Lynches Creek was known as a meeting site for the Regulators, a group of vigilantes who used violence against their opponents. These early definitions of lynching refer to forms of frontier vigilantism.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, lynching took on a new, racial connotation and was primarily carried out by whites against African Americans. This racial violence gave white southerners a way to express and reaffirm their white southern identity. It also deterred African Americans from attempting to assert the equality granted to them under the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Lynching became so widespread that the years 1882 to 1930 have been termed the “lynching era.” The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) defined lynching during this period as murder committed extralegally by three or more persons who claim to be serving justice. Between 1882 and 1930 the number of lynching victims in the South totaled 2,805. South Carolina, with 156, had the second-fewest lynching victims. Mississippi, with 538 victims, had the most. [The Equal Justice Institute’s 2017 report on lynching documents 185 reported lynchings in South Carolina.]

The justifications for mob violence had little regional variation across the South as they shared the common intention of disenfranchising blacks. During this era, drawing on scientific racism, white southerners created and articulated an image of African American males as black, beastly rapists whose animal-like sexuality threatened white women’s purity. White men claimed that lynching was a way to protect themselves and, more importantly, their women from black aggression. Racial violence offered white southerners a chance to “redeem” southern society, restoring it to its pre-Reconstruction state. South Carolina governor Benjamin Tillman represented these beliefs about African Americans and southern white male responsibilities. In 1892 Tillman spoke of his own willingness to lead a lynch mob against any black man who had been accused of raping a white woman.

Antilynching advocates, such as Ida B. Wells and Jesse Ames of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, revealed that contrary to white claims, the majority of lynch victims were not accused of raping white women. In actuality, only nineteen percent of black victims in the South were accused of rape. Victims were lynched for a wide range of behavior, including such illegalities as murder, theft, arson, and assault, as well as for such disrespectful actions as trying to vote, being disruptive, and frightening a white woman.

South Carolina was the site of one of the largest lynchings. On December 28, 1889, in Barnwell County eight African American men were accused of murdering a local merchant. A mob broke them out of jail, tied them to trees, and then shot them. In 1926 Aiken was the site of the Lowman family lynching. A sheriff and his deputies, all members of the Ku Klux Klan, arrived to arrest one of the Lowman sons. Upon hearing that the boy was gone, the sheriff attacked his sister. The resulting scuffle ended with mother Lowman shot by the sheriff, who in turn was killed by a stray bullet. The remaining Lowmans were arrested and tried. When one brother was acquitted, a Klan-led mob stormed the jail, dragged them out, and shot them.

The last lynching in South Carolina occurred on February 17, 1947, when a white mob murdered Willie Earle, a young black man who had been arrested for murdering a white taxicab driver. Although those responsible were acquitted, Earle’s murder marked a turning point for lynching in South Carolina. State and federal law enforcement agents conducted an intensive investigation of the crime that resulted in several arrests and a vigorous prosecution of the accused.

The Earle murder was the culmination of a decline in lynching that occurred during the 1930s and 1940s, which reflected a larger social change. The “Great Migration” of African Americans to northern cities in the 1930s changed labor dynamics in the South. Lynchings, which previously were a form of punishment for interpersonal violence, became a form of social repression, targeted not at criminals but at successful African Americans. By the 1940s the social dynamics that had allowed whites to lynch without fear of repercussions were effectively gone, and so gradually the lynching era came to an end.

— Excerpted from an entry by Kristina Anne DuRocher. To read more about this or 2,000 other entries about South Carolina, check out The South Carolina Encyclopedia, published in 2006 by USC Press. (Information used by permission.)

ABOUT STATEHOUSE REPORT

Statehouse Report, founded in 2001 as a weekly legislative forecast that informs readers about what is going to happen in South Carolina politics and policy, is provided to you at no charge every Friday.

- Editor and publisher: Andy Brack, 843.670.3996

- Statehouse correspondent: Lindsay Street

More

- Mailing address: Send inquiries by mail to: P.O. Box 22261, Charleston, SC 29407

- Subscriptions are free: Click to subscribe.

- We hope you’ll keep receiving the great news and information from Statehouse Report, but if you need to unsubscribe, go to the bottom of the weekly email issue and follow the instructions.

© 2018, Statehouse Report. All rights reserved.