NEWS: Coverage gap could halt Medicaid work requirement in South Carolina

BRIEF: Income taxes low in S.C., but you may not want a beer to celebrate

CALENDAR: Budget remains on hold but look: Art!

COMMENTARY, Brack: 2018 brings more House contests, but not lots of women candidates

SPOTLIGHT: Riley Institute at Furman University

MY TURN, Bryant: S.C. still awaits true ethics reform

FEEDBACK: Send us your thoughts

MYSTERY PHOTO: Red brick building stands out on sunny day

S.C. ENCYCLOPEDIA: Ferries

NEWS

NEWS: Coverage gap could halt Medicaid work requirement in South Carolina

By Lindsay Street, Statehouse correspondent | While the Trump administration has given the green light for states to restrict Medicaid access by requiring recipients to work, there’s a catch that could derail the effort in South Carolina.

The four states that have gained approval for work requirements have expanded Medicaid programs. That puts South Carolina in a bind because it would have to offer Medicaid to cover more poor people if it wanted to further restrict who can become a beneficiary.

But Gov. Henry McMaster’s office has said he will not expand coverage even if it means achieving his administration’s goal of requiring able-bodied adults to work to receive benefits:

“Under no circumstances will Governor McMaster approve of expanding Medicaid in South Carolina, but he does plan to continue pursuing the waiver that would require able bodied adults to work or give back to the community in some way in order to receive Medicaid benefits,” McMaster spokesman Brian Symmes said in a statement to Statehouse Report this week.

McMaster tasked S.C. Department of Health and Human Services in January to obtain federal authority to exclude jobless adults from Medicaid coverage. A draft of the plan was completed in early April and it seeks to require working-age beneficiaries, who are not pregnant or disabled to work, go to school or volunteer to receive benefits. If approved, the state agency wants to enact it beginning Jan. 1, 2020.

Beginning last year, the Trump administration started allowing states to seek waivers and implement plans that would make employment be a requirement for Medicaid eligibility. The Centers on Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) trumpets the work requirement as “community engagement” and a way to increase health of a community through incentivizing gainful employment or volunteering. Kentucky, Arkansas, Indiana and New Hampshire have received approval so far. CMS is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Those paying close attention to CMS’s communications say the agency is only approving waivers in states where there are no health coverage gaps between Medicaid and federally-subsidized insurance. All four states with approved waivers have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

The former head of the state’s Medicaid agency, Christian Soura, said CMS has “strongly signaled” publicly and behind closed doors in talks with state officials that those states gaining waivers to require work requirements for beneficiaries must have expanded Medicaid coverage or very few people found in coverage gaps.

“That’s the only version of the work requirement that they’re going to approve in this state,” said Soura, who now is vice president of policy and finance at the S.C. Hospital Association. “Non-expansion states will not get work requirement waivers approved”

Joshua Baker, the current head of S.C. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS),told Statehouse Report this week that while the approving agency has only given waivers to expansion states, it has not explicitly said it would deny non-expansion states. Still, he said, it could be a factor in the decision for South Carolina.

“We’re making the reasonable assumption we are able to apply for this waiver under the current model,” Baker said Thursday. “Every state’s Medicaid program is unique.”

It’s not unheard of for a GOP-controlled state to later expand Medicaid coverage. This week, Virginia’s lawmakers approved expanding Medicaid there after a shift from Republicans to Democrats. There, four Republicans broke ranks to approve expansion. But it’s considered to be an unlikely move in deeply-red South Carolina with current leadership. This week, Democratic gubernatorial candidate James Smith released an ad this week pushing for expansion of Medicaid.

The coverage gap

South Carolina is one of 18 states that did not expand coverage through Obamacare. And it’s no secret that South Carolina has a chasm filled with those who make too much to receive Medicaid but not enough to be able to afford to purchase subsidized insurance on the marketplace.

Adults in the state who are able to qualify for Medicaid must earn below 67 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2017, the federal poverty level was $13,860 for a single person. That means a Medicaid beneficiary would need to earn less than $10,000 per year to qualify in South Carolina. If a person’s income exceeds 100 percent of poverty, then he or she is eligible for subsidized health insurance.

People who fall in the Medicaid eligibility gap earn between 67 percent and 100 percent of poverty, which represents about 6 percent of households in South Carolina. Meanwhile, DHHS estimates 180,000 South Carolinians who currently receive Medicaid in the gap through Obamacare could be impacted by the waiver’s implementation to end coverage to non-employed beneficiaries.

However, many Medicaid beneficiaries are already work, according to Palmetto Project Executive Director Steve Skardon.

“It’s kind of hard to imagine who these able-bodied people are who are receiving Medicaid and not working,” he said. He likened the not-working Medicaid-eligible person to those committing voter fraud, who “it turns out, they didn’t exist.”

Skardon had harsh words for any work requirement for Medicaid beneficiaries.

“This seems like an extremely expensive exercise that does not yield any practical results,” he said.

South Carolina’s proposal

South Carolina’s draft plan to add a work requirement for Medicaid, while bereft of specifics for implementation, spells out the state’s intentions should the plan be approved. The state wants to limit eligibility to individuals who are “employed, enrolled in a qualified education program, or who are participating in a qualified community engagement activity.” There would be exceptions for those who are pregnant or disabled.

The requirements would piggyback off of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, which already require community engagement for benefits. Already, according to the draft, more than half of Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in either program.

It’s that piggyback that would help with cost savings, according to Baker. The programs would have to merge into a single system, he said.

The cost

Meanwhile, a recent report from the Center for Budget and Public Policy, a national think tank, warns that states seeking waivers could face tens of millions in expenses in implementation and possibly hire additional staff with recurring expenses. The consolation, according to the report, is that states would save money by losing beneficiaries who no longer qualify for Medicaid.

Examples cited in the report include:

- Kentucky’s estimate of spending $186 million in fiscal year 2018 and an additional $187 million in 2019 to implement its approved waiver;

- Alaska’s projected cost of $78.8 million over six years, including about $14 million per year in annual ongoing costs; and,

- A Pennsylvania state official saying it would cost $600 million and require 300 additional staff to administer.

![]() South Carolina officials have no such estimates, and Baker said he doubted the price tag would be so steep. He said Medicaid, SNAP and TANF need to modernize their systems anyway.

South Carolina officials have no such estimates, and Baker said he doubted the price tag would be so steep. He said Medicaid, SNAP and TANF need to modernize their systems anyway.

“We want to use this as an opportunity to modernize the systems in existence today,” Baker said. “That’s something the state needs to do whether we get this waiver or not.”

He also said no additional employees would need to be hired.

Others, like Soura, disagree that it will be cost-effective to implement the work requirement.

“The administration costs are undoubtedly in the millions; realistically, they are almost certainly in tens of millions,” Soura said. He broke down the total cost into a significant, one-time cost of the eligibility software system and the recurring expense of hiring “a whole bunch” of people to administer the program.

South Carolina’s current focus is obtaining a waiver from CMS that will allow it to end Medicaid dollars to abortion-providing clinics by requiring providers give “preconception care.” Baker said once that waiver is decided, it will shift focus on the work-requirement waiver. In the meantime, the state has begun talks with stakeholders and will continue drafting a plan for submission to CMS.

- Read more about how the plan to defund Planned Parenthood could expand services for Medicaid beneficiaries in South Carolina.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com

NEWS BRIEFS

BRIEF: Income taxes low in S.C., but you may not want a beer to celebrate

![]()

Staff reports | The Tax Foundation released two reports this week that offer a mixed bag for South Carolina: The state has the 15th lowest income taxes in the nation, but the seventh highest beer tax in the nation.

South Carolina is one of 41 states that levy a tax on an individual’s income. Only seven states offer no income tax: Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming.

South Carolina collects $764 in income tax for each S.C. resident, according to the report. New York collected the most per capita at $2,781.

Meanwhile, all states levy taxes on beer. South Carolina’s tax comes out to about $0.77 per gallon. The Southeast has among the highest beer taxes in the nation. Tennessee has the highest beer tax at $1.29 per gallon. Wyoming has the lowest beer tax at $0.02 per gallon.

In other beer-related news, federal tariffs on aluminum could soon impact beer prices around the country.

CALENDAR: Budget remains on hold but look: Art!

![]() Staff reports | South Carolina lawmakers aren’t expected to meet to hash out details of the state’s $8 billion spending plan until after the June 12 primary, which means another week of campaign rhetoric with little action.

Staff reports | South Carolina lawmakers aren’t expected to meet to hash out details of the state’s $8 billion spending plan until after the June 12 primary, which means another week of campaign rhetoric with little action.

But while House members and other candidates are hitting the campaign trail hard in the final days before the primary, two arts-focused festivals are offering a break from the political (unless candidates are handing out brochures at the events).

- The Ag + Art Tour begins Saturday with tours this weekend in Chesterfield, Darlington , Florence, Horry and Kershaw counties. South Carolina Ag + Art Tour is a free, self-guided tour of designated farms in South Carolina featuring local artisans and farmers markets. Click here to learn more.

- In Charleston, Spoleto Festival USA is continuing this weekend through next week. The major performing arts festival features many kinds of performances. Saturday features music by Gullah-inspired band Ranky Tanky. Click here to see a schedule. The City of Charleston’s companion festival, Piccolo Spoleto, offers hundreds of events.

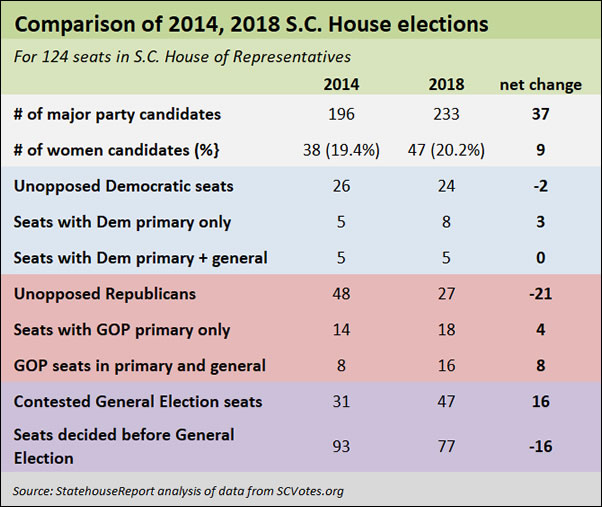

BRACK: 2018 brings more House contests, but not a lot more women candidates

By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | It may be the Year of the Woman in politics around the nation, but not in South Carolina – at least not in races for the S.C. House of Representatives

In 2018, just over 20 percent of major party candidates in the 124 House races are women, according to a Statehouse Report analysis of state election data. Four years ago, there were nine fewer women candidates as 38 women (19.4 percent of candidates) ran for House seats.

College of Charleston political scientist Gibbs Knotts said he is surprised more women aren’t running for state House seats, particularly with a heightened energy by women about politics and organizing since President Trump was elected in 2016.

“South Carolina has the seventh lowest percentage of women state legislators in the country so there is certainly room for growth,” he said, noting a 2018 study by the Center for American Women in Politics at Rutgers University.

But he added that South Carolina’s traditional political culture as well as discrimination against women might be reasons more women aren’t running for the House here.

While the number of female candidates running in 2018 isn’t markedly different in House races, three things stand out:

Fewer unopposed Republicans. Four years ago, 48 Republican House candidates had no opposition in the primary or general election. This year, that number dropped almost in half to 27 unopposed candidates.

More contested GOP primaries. Fewer unopposed races, means more contested ones. In 2018, a dozen seats have GOP candidates who will face a primary or a primary plus a general election Democratic opponent. Why the change? More than likely, it’s because more conservative candidates emboldened by Trump are trying to drain the Statehouse swamp of already-conservative GOP House incumbents.

More contested races in November. The dynamics of politics this year reveal there will be fewer seats – 77 – decided before the general election, compared to three quarters of seats in 2014. That means voters have more choices in November. But it’s still a little disturbing that more than half of the seats don’t face general election competition, an indicator of gerrymandering at play.

“There’s a lot of interest in politics right now, thanks to Trump and some divisions within the Republican Party nationally and locally about the direction the party should go,” said Danielle Vinson, a political scientist at Furman University. “ Some of those pre-date Trump, but he has certainly exacerbated them. So, that may be driving some of the increased interest in running for office among Republicans and would explain the increase in the number of Republican incumbents facing primary challenges.”

She thought, however, some incumbents just seem to attract primary challengers, regardless of the political environment, or because they’re relatively new in office, which may draw challengers who smell weakness or opportunity.

“We learned in 2016 that incumbents can be vulnerable in primaries in South Carolina if they’ve taken controversial votes or missed a lot of votes,” Vinson said. “We lost a lot of incumbents that year.”

Knotts made a similar observation: “I suspect incumbents are being ‘primaried’ by more conservative candidates. There is probably a Trump effect taking place and there could be some backlash against the corruption probe in Columbia and the increased gas tax that was passed in 2017.”

If you’re a little miffed that 62 percent of House seats will be decided before the general election by members of one major party or the other, there are at least two options:

Run for office. The more people who run give more choices to voters, particularly in primaries. If the major parties disgust you, there are always third parties. Unfortunately, they currently fare so poorly that the state has no third-party elected officials.

Attack gerrymandering. The General Assembly will decide how House, Senate and congressional seats are drawn after the 2020 Census. If you want districts to be more competitive and reflective of how politics are in your area, you need to work or donate to organizations that want to defeat or alter the good-old-boy way districts are drawn.

Democracy is stronger when it is competitive. What we’re generally doing now is just protecting incumbents and encouraging the edges of politics, not promoting the common good.

- Have a comment? Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

SPOTLIGHT

SPOTLIGHT: Riley Institute at Furman University

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is The Richard W. Riley Institute of Government, Politics, and Public Leadership, a multi-faceted, non-partisan institute affiliated with the Department of Political Science at Furman University. Named for former Governor of South Carolina and United States Secretary of Education, Richard Riley, the Institute is unique in the United States in the emphasis it places on engaging students in the various arenas of politics, public policy, and public leadership.

The public spiritedness of our underwriters allows us to bring Statehouse Report to you at no cost. This week’s spotlighted underwriter is The Richard W. Riley Institute of Government, Politics, and Public Leadership, a multi-faceted, non-partisan institute affiliated with the Department of Political Science at Furman University. Named for former Governor of South Carolina and United States Secretary of Education, Richard Riley, the Institute is unique in the United States in the emphasis it places on engaging students in the various arenas of politics, public policy, and public leadership.

- Learn more about the Riley Institute.

- Also learn more about the Riley Institute’s Center for Education Policy and Leadership.

BRYANT: S.C. still awaits true ethics reform

By Lt. Gov. Kevin Bryant, special to Statehouse Report | Political corruption in Columbia is worse now than ever. The simple bribery from the Lost Trust era has been replaced by actual organized crime complete with a godfather and loyal family. Our ethics laws, unfortunately, simply are not up to fighting this kind of crime.

![]() Earlier this year, I authored the South Carolina Anti-Racketeering Act, a bill to fight organized crime by giving our law enforcement the same tool used by the FBI to tackle the Mafia. Thirty-three other states also have this law and it is sponsored by members of both the House and Senate.

Earlier this year, I authored the South Carolina Anti-Racketeering Act, a bill to fight organized crime by giving our law enforcement the same tool used by the FBI to tackle the Mafia. Thirty-three other states also have this law and it is sponsored by members of both the House and Senate.

Political lobbyists, following Operation Lost Trust, figured out that they could create a network of power if they served as “consultants” to candidates and elected officials, oversaw their mail and fundraising, and charged them for polling. Successful operatives not only made huge sums of money but also grew their political family.

Once a political family had enough members in the right places, the head of the family then could take on other “clients” with business at the Statehouse with the promise that their family members would act appropriately.

The most successful don, Richard Quinn, eventually became known as The Godfather. He served as the political consultant for several powerful members of the General Assembly and several members of the executive branch, including lieutenant governors, attorneys general and others.

Quinn openly spoke of his “political family,” and I imagine those words were emphasized when he spoke to non-elected clients such as SCANA and other large corporations from whom he extracted millions of dollars, also for “consulting.”

Perhaps the most impressive feat occurred when Quinn engineered the election of his own son, “Rick,” to the S.C. House. The younger Quinn even became majority leader and finished out his service (more on that later) as a member of the Ways and Means Committee. The “Quinndom” wielded tremendous power inside and outside the Statehouse.

Through a sequence of events generated by the corruption investigation of former House Speaker Bobby Harrell, the Quinndom fell under the microscope of a special prosecutor who was named to the case because the original prosecutor, the attorney general, is a Quinn “client.”

The prosecutor uncovered a pattern of The Godfather taking money from special interests and then the elected officials whom he “consulted” acting in ways to benefit those clients. Some of them even admitted it in email.

This led the prosecutor to indict Rick Quinn and other political family members. The prosecutor said that The Godfather “used legislators, groomed legislators and inspired legislators and others to violate multiple provisions of the state ethics act so they could all make money.”

But the indictments were for “misconduct in office,” a very vague and hard to prove standard. The prosecutor added charges of “criminal conspiracy,” but the conspiracy pertains to the misconduct charge; again, vague and hard to prove.

My bill allows for the prosecution of the pattern of behavior, itself. That is the racketeering. Racketeering is at least two acts in furtherance or one or more schemes that have similar intent. The “acts” include violations of the ethics and lobbying laws.

The bill also prevents a lobbyist from working for a campaign for two years and from ever being paid by any state agency. The bill further prohibits a former public official from ever serving as a lobbyist, and they would have to wait two years before working or serving another candidate’s campaign.

More disclosure, more donation caps and even term limits are fine, in and of themselves, and I support them. But, organized crime in South Carolina is smarter than that. We need the right tool for the job, and my anti-racketeering bill is the place to start.

Kevin L. Bryant, a former state senator from Anderson, is the 92nd lieutenant governor of South Carolina. He is running to be the state’s next governor. More: KevinBryant.com.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Through June 12, Statehouse Report is running opinion pieces by gubernatorial candidates with primary challengers. Five Republicans and three Democratic candidates for governor have been invited to submit messages they want to share with voters.

Recent candidate contributors

- GOP, McGill: South Carolina is worth fighting for(April 19)

- GOP, Templeton: “The called me the ‘Buzzsaw’”(May 3)

- GOP, Warren: “We deserve better from our leaders” (May 10)

- DEM, Willis: People run for office for lots of reasons(May 16)

- DEM, Noble: “It is never too late to do what we know is right” (May 21)

- GOP, McMaster: Fighting to achieve our full potential (May 25)

- Have a comment? Send it to: feedback@statehousereport.com.

FEEDBACK

FEEDBACK: Send us your thoughts

We love hearing from our readers and encourage you to share your opinions. But you’ve got to provide us with contact information so we can verify your letters. Letters to the editor are published weekly. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity. Comments are limited to 250 words or less. Please include your name and contact information.

- Send your letters or comments to: feedback@statehousereport.com

MYSTERY PHOTO

MYSTERY PHOTO: Red brick building stands out on sunny day

This week’s mystery is a tidy brick building resplendent on a sunny day with a bright, blue sky. Send your best guess – plus your name and hometown – to feedback@statehousereport.com. In the subject line, write: “Mystery Photo guess.” (If you don’t include your contact information, we can’t give you credit!)

Our previous Mystery Photo

Few guesses came in for the most recent mystery photo thanks to (&#@!%&*!) technological travails related to an email address that was down for the week. That’s been fixed (thank goodness!), but many of you may be frustrated that your guess didn’t get to us.

Few guesses came in for the most recent mystery photo thanks to (&#@!%&*!) technological travails related to an email address that was down for the week. That’s been fixed (thank goodness!), but many of you may be frustrated that your guess didn’t get to us.

Several people guessed the photo to be Indian Land campground in Dorchester County while one diehard Carolina wag identified the buildings as Clemson dorms!

Nope. The photo is of the Cattle Creek Methodist Campground in Orangeburg County. Thanks to Bill Segars of Hartsville who allowed us to publish his photo. “The main giveaway is that the Indian Field tents are built in a circle,” Segars said. “Cattle Creek tents are built in a square. The structures look very similar.”

Hats off go to George Graf of Palmyra, Va., who correctly identified the photo. He noted, however, “Seems there are many of these places that are so similar. Tough to isolate the little differences to determine which is the matching answer. I’m not positive, but I’m going with this answer.”

Send us a mystery: If you have a photo that you believe will stump readers, send it along (but make sure to tell us what it is because it may stump us too!) Send to: feedback@statehousereport.com and mark it as a photo submission. Thanks.

S.C. ENCYCLOPEDIA

HISTORY: Ferries

S.C. Encyclopedia | The earliest ferries in South Carolina carried settlers across the Ashley, Cooper, Santee, and other Lowcountry waterways. Early ferries, sometimes called “boats” or “galleys,” were important for transportation but were frequently poorly constructed, haphazardly manned, and expensive to the everyday traveler. Accordingly, the General Assembly in 1709 passed the first of many laws governing the location, management, and fees associated with ferries. Under the law, the ferry master was to provide for the passage of one man at one pence and a “man and horse from one side of [the river] to the other” at a cost of two pence. Most ferries took the name of an early licensee: Mazyck, Skrine, Garner, Vance, Murry, or Nelson. Others were known only by the location: Strawberry Ferry, Ashley River Ferry, or South Island Ferry. One, across the Black River, was referred to only as the “Potato Ferry.”

The first boats were large canoes or flat-bottom scows that were powered by paddles, oars, or poles. Within one hundred years, flatboats capable of holding a wagon or carriage had become commonplace. The heavier load necessitated a pulley/winch system to move the flatboat and cargo against the current, and costs rose accordingly. In 1805 the toll on a team or carriage was $1.00, and a man and horse was 12.5¢. A barrel of freight was 25¢.

Ferry operations in antebellum South Carolina were closely regulated by the General Assembly, which established rates of toll and the duties of ferry operators. Negligent operators or those who attempted to extort higher tolls could be fined or have their ferry licenses taken away. The General Assembly could not, however, regulate nature. Floods, drought, and storms frequently interrupted ferry operations. Still, with bridges difficult to build and expensive, ferries were a vital link in the state’s transportation system throughout the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth centuries. Their number increased from several dozen crossings in 1775 to more than one hundred by 1825. As the state’s population spread inland in the early nineteenth century, ferries became increasingly prevalent in the backcountry.

The destruction or elimination of all but twenty ferries by 1865 was the beginning of the end for the institution. Steamboats and railroads lessened the need for ferries throughout the nineteenth century, while the arrival of the automobile finished it off in the twentieth century. Formed in 1917, the South Carolina Highway Department utilized taxes on automobiles, automobile dealerships, and gasoline to build the state’s first system of modern roads and bridges. With the assistance of federal money, South Carolina acquired thousands of miles of new roads and hundreds of bridges. A few ferries persisted until well into the twentieth century, such as Ashe’s Ferry at Van Wyck or Scott’s Ferry on the Savannah, but most were replaced by bridges. Places such as Givhans Ferry State Park in Dorchester County and Galivants Ferry in Horry County, however, provide reminders of the prevalence and importance of ferries in the state’s transportation history.

— Excerpted from an entry by Louis P. Towles. To read more about this or 2,000 other entries about South Carolina, check out The South Carolina Encyclopedia, published in 2006 by USC Press. (Information used by permission.)

ABOUT STATEHOUSE REPORT

Statehouse Report, founded in 2001 as a weekly legislative forecast that informs readers about what is going to happen in South Carolina politics and policy, is provided to you at no charge every Friday.

- Editor and publisher: Andy Brack, 843.670.3996

- Statehouse correspondent: Lindsay Street

More

- Mailing address: Send inquiries by mail to: P.O. Box 22261, Charleston, SC 29407

- Subscriptions are free: Click to subscribe.

- We hope you’ll keep receiving the great news and information from Statehouse Report, but if you need to unsubscribe, go to the bottom of the weekly email issue and follow the instructions.

© 2018, Statehouse Report. All rights reserved