By Andy Brack, editor and publisher | There’s one word for Gov. Henry McMaster’s proposal for a huge state income tax cut: Irresponsible.

It might sound great – a $2.2 billion tax cut over five years. But face it: South Carolina still has a revenue problem. Just look at our continually lagging schools, dangerous prisons, inadequate health care system. These things take money to fix, not less money.

McMaster’s political gambit is nothing but election-year pabulum for voters who want the benefits of government without having to pay for it. McMaster may not even really care if the legislature approves the tax cut. If it doesn’t, then he can campaign that he proposed it and then politick against the General Assembly, like predecessor governors Mark Sanford and Nikki Haley.

This tax cut proposal is right out of the GOP playbook in South Carolina. People shouldn’t fall for it. Governance isn’t easy and things actually do cost money in government, just like in business or for families. At work, people know investments often fuel change. At home, they know investing in college and better education helps kids get a leg up. Why not with state government? Because pandering politicians too often promise the world at no cost.

What’s particularly annoying about McMaster’s disappointing and cynical gimmickry is that voters have already received billions of dollars of state tax cuts in recent years.

South Carolina’s motto is “dum spiro spero,” or “While I breathe, I hope.” But these days, it seems the real motto is “Dumb spiro spero,” which means, “While I breathe, I hope we’re not this dumb.”

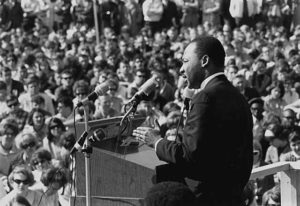

WITH THE MARTIN LUTHER KING holiday approaching, it’s a good time to look at how South Carolina influenced King – and how he influenced the Palmetto State.

WITH THE MARTIN LUTHER KING holiday approaching, it’s a good time to look at how South Carolina influenced King – and how he influenced the Palmetto State.

Many people don’t realize South Carolina provided sanctuary for King and his supporters. He used Penn Center on St. Helena Island as a retreat to think and compose. While state officials in many parts of the South interfered with King, his South Carolina base for reflection helped usher in the civil rights movement.

“His main personal contact with the state was staying at Penn Center to write his books,” says historian Jack Bass of Charleston. “There was always an FBI agent down at Penn Center or just outside of it (because) that was in the J. Edgar Hoover era (of the FBI) and he thought King was a communist.”

Charleston’s Septima Clark also had a big influence on King by working with his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to develop and spread citizenship schools across the South. They registered hundreds of thousands of black voters. Clark was so appreciated by King that she attended the 1964 ceremony in which he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

But King, who made few public appearances in the Palmetto State, also influenced South Carolina. In a 1962 sermon at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, King urged blacks to register to vote, which he then said was key to making the “American dream a reality” for blacks.

Four years later after passage of the federal Voting Rights Act, King emphasized the power of voting to a crowd of 5,000 in Kingstree on Mother’s Day. In what is known on the “March of Ballot Boxes” speech, King said, “Let us march on ballot boxes, until somehow we will be able to develop that day when men will have food and material necessities for their bodies, freedom and dignity for their spirits, education and culture for their minds.”

In a July 1967 speech at Charleston’s County Hall, King urged blacks to refrain from violence and riots that were impacting some American cities. He said, “The reason I’m not going to preach a doctrine of black supremacy is I’m so sick and tired of white supremacy.”

In February 1968, five days after the Orangeburg Massacre at then-S.C. State College, King urged U.S. Attorney General to get to the bottom of the “largest armed assault undertaken under color of law in recent Southern history.”

Less than two months later, King was shot to death in Memphis. He was just 39.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968). Rest in peace.

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!

We Can Do Better, South Carolina!