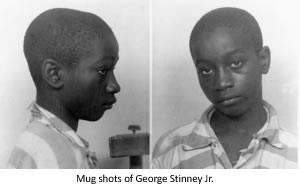

There’s a learning moment for South Carolina lawmakers in the case of George Stinney Jr., the 14-year-old Clarendon County boy railroaded to execution in 1944.

![]() A Beaufort County judge on Dec. 16 vacated the murder conviction of the young African American teen-ager. In April 1944, just a month after being arrested for the deaths of two white girls, an all-white jury spent 10 minutes deliberating after a two-hour trial before convicting Stinney. His court-appointed defense lawyer mostly stood by, filing no appeals or requests for a stay of execution. In June, less than three months after the murders, the state electrocuted Stinney, the youngest person executed in the country in the last century.

A Beaufort County judge on Dec. 16 vacated the murder conviction of the young African American teen-ager. In April 1944, just a month after being arrested for the deaths of two white girls, an all-white jury spent 10 minutes deliberating after a two-hour trial before convicting Stinney. His court-appointed defense lawyer mostly stood by, filing no appeals or requests for a stay of execution. In June, less than three months after the murders, the state electrocuted Stinney, the youngest person executed in the country in the last century.

It was another lowlight of the Jim Crow South. Stinney’s family fled Clarendon County, just like others did a few years later after black parents filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn “separate but equal” education. That case, first filed in 1947, was the foundation of the landmark Brown v. Board decision by the U.S. Supreme Court that ended segregated schools.

Circuit Judge Carmen T. Mullen vacated the Stinney conviction based on a 600-year-old legal remedy of common law that is so rarely used that many have never heard of it. The extraordinary remedy, called a writ of coram nobis, was applicable because of fundamental due process errors that aren’t generally found in modern cases. In the Stinney case, for example, the writ was used because the conviction “was obtained by unfair or unlawful methods and no other corrective judicial remedy is available.” (Read Judge Mullen’s ruling.)

Anyone worrying that inmates incarcerated today in jails and state prisons will flood courts using this due process writ shouldn’t get hot and bothered. It won’t apply because there are lots of other judicial remedies available.

But what should be instructive to citizens and especially state lawmakers is that South Carolina has finally recognized that it did something very wrong 70 years ago as America was focused on the D-Day invasion of France in  World War II. This week’s ruling won’t bring back George Stinney Jr. It won’t erase the fact that the teen’s family never saw him alive again after he was arrested in March 1944 — not while he sat afraid in jail, not during the trial and not as he waited to die.

World War II. This week’s ruling won’t bring back George Stinney Jr. It won’t erase the fact that the teen’s family never saw him alive again after he was arrested in March 1944 — not while he sat afraid in jail, not during the trial and not as he waited to die.

The ruling, however, does accomplish two things. First, it provides some solace and closure to family members who are still alive. And second, it shows how South Carolina can face its past and admit a wrong.

The South Carolina General Assembly can lead the way. There are dozens of problems in this state that are legacies of Jim Crow days that have never been effectively battled. It’s time to right those wrongs, once and for all. It’s time to do more than just what businesses and special interests want. It’s time to provide good opportunities for the downtrodden, the “least of these” as described in the Book of Matthew.

Wondering where to focus? Just look the state’s high poverty rate, challenged education system and high incarceration rate (13th highest in the country at 473 prisoners per 100,000 people in 2011).

“Overt racism of 70 years ago in treatment of George Stinney unfortunately lingers today in institutions,” said Victoria Middleton, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of South Carolina. “We continue to see more children of color bear the brunt of harsh school discipline practices and juvenile sentencing.”

It’s uncomfortable for many to talk about race and the enduring effects of racism. But from a policy perspective, it’s time to move forward and look at institutional racial disparities across the Palmetto State. And for that, state lawmakers should lead the way.

“Education is the one area where the legislature can have the most immediate impact — to commit dollars to right a 100-year-old wrong,” said the Rev. Joseph Darby, a presiding elder with the AME church and longtime Charleston civil rights activist.

Our state’s leaders need to broaden their policy focus beyond partisan politics. They need to think beyond labels and hot-button issues. Now is the time to absorb the big picture and then focus on proactive ways to shed the legacies of the past.